go ahead to: [section II]; [subsection 166]; [167]; [168]; [169]; [170]; [171]; [172]; [173]; [174]; [175]

II. the ‘fourth

attempt’ itself

166. a new kind of

upset for the Lorenzos: Mortimer’s new ‘book’

By the

first few pages of the ‘fourth attempt’, though, most ‘drastic

lunacy’ like 'bi-bodihood' seemed to have faded away, as Jo

sighed to Rev. Events described in the ‘fourth attempt’ seemed

‘more likely to have happened’ than the psych ward in Fort

Smith. All too possible,

in fact, as the Lorenzos would feel by the end of the section.

And so, ‘drastic lunacy’ WAS ‘a thing of the past’.

They were right,

this time. ‘Mild craziness’ was all that hung in the air. But

that, unfortunately, would only produce a different kind of

upset, soon enough.

The

‘fourth attempt’ opened with a strange description of ‘mj’ and

his supposed physical reality. Then, a strange dream.

But,

‘All dreams seem strange at first’, as Jo conceded.

And: ‘Physical reality is not

what it’s Cracked Up to be, as often as not’, said Rev.

And the pun pundits would give Rev a pun prize for this

brilliant twist on mj’s famous term, ‘Crack-Up’, finally

granting it posthumously in 2003, seventeen years after the

Reverend’s death; and partly because he was ‘brilliant enough’

to capitalize the ‘C’ and the ‘U’, as proven by the margin of

his notes for that Sunday’s sermon shown to them by Jo.

But

‘the point was’, as Rev and Jo complained to each other after

reading the whole section: the opening pages of the ‘fourth

attempt’ did not

prepare one adequately for what was to follow

within that section. The introductory paragraph did succeed in

‘throwing them both for a loop’ for a second, Rev AND Jo both,

true. But only for a

second, because their son had played cat and mouse with

his ‘location and condition’ too many times since he had

stolen the car and vanished. They had grown bored with the

game by now. They dismissed it and kept reading, evidently

proving how much havoc mj lorenzo could wreak on a

strait-laced neo-Calvinist psyche in one year and get away

with it. For: the Lorenzos, against their wishes, had finally

become converts to

the un-parent-like belief that a son’s physical location and

condition were not important. And their conversion

barely dawned on them or upset them, either, at first. That’s

how thorough and cleverly wrought by their son the conversion

had been.

Mj’s

left

arm is thrust outward in an airplane splint, while the other

remains free to make notes, hand signals, or love (!), as he

chooses. A window is cut in the cast at the left shoulder,

baring it for intramuscular injections of morphine. Several

hours after one of his periodic shots, mj scribbles down the

following in one breath, so to speak:

Mj

had driven his father’s Buick to a new section of town and

run into some hospital nurses in a soda fountain, who were

teasing and tormenting him as he walked toward them. He

approached the counter and weighed the stool arrangement.

Here there were two stools together, but next to one of them

sat a corpulent, overbearing nurse; and he shuddered as a

destructive urge escaped his spinal cord and bolted to the

base of his back. At the far corner of the counter were two

empties together, then a single taken, then two more

empties. But he wanted to sit with nobody next to

him. They had baked a type of ravioli which a

barker tried to sell him, with his grey flimsy greasy

cardboard box of red and white fleshy pasta opened on top of

one of the stools.

Why

wouldn’t they let him sit for a soda alone in peace?

He

got in his car and drove off, and stopped…. at an obstacle,

a precipice. Or maybe he had run into the dump, a wall of

trash and garbage. It was barren, wasted, loose, dusty,

dull, grey-white soil on all sides strewn with human refuse.

As he backed down a two-lane road, anger welling within him,

suddenly and finally rage

overtook him and drove him out of control in reverse

as the car swerved abruptly left and right and his frantic

correction of the wheel increased the chaos and he flashed

on the unknown number of drivers who commit suicide by auto

crash and considered that this was a common mode of

self-annihilation, judging from the excess of crack-ups in

which lone drivers (or did he imagine a pretty girl in the

back?) dove off the road embalmed in their cars and strenuously

– for he half-decided he really wanted to dis-involve

himself – he stretched toward the right side while he and

the car continued hurtling backward accelerating, though his

foot was off the pedal, his left hand lingering frozen stuck

to the wheel as his right played with the right door handle

and he studied the earth and daylight flying beneath the

door crack like a movie on rapid rewind which way was he

to jump was he to run against or with

the car or jump straight out?

It

was taking too long to decide to overpower his indecision

and the car’s momentum itself as he was under its spell

could not escape the reel too quickly rewound would make his

exit anyway, and he LEAPT; and Kierkegaard’s Leap of

Faith left a world behind and made him half a person; with

the car’s direction but on an angle out from it and

plummeted on feet then in air and then upside down with

occasional limbs striking or scraping and finally all of him

skidding to a backbreaking halt in a cloud of white dust and

splattering garbage and he became aware of his fright and

the rate of his heart beat, the sound of low noise-level

distant rumbling truck traffic, a bed beneath his aching

back, then his blankets and clean sheets and pillow, then of

the fact that he had been the subject of a vicious dream,

then again of the truth that he was paralyzed with terror.

And finally, he began to wonder about the dream itself.

Poor

mj had never been quite so acutely aware of his body.

But

had he had a body

in that dream?

Had

it been a blue Buick Electra that had crashed? Had the car

bent in half and exploded when it ran into a wall of hill

after he jumped? Was there or was there not a certain person

in the back? Why should he want to sleep now and forget such

questions? How could his body perform what his mind did not

conceive first, or his mind conceive of what his body flatly

rejected? He felt trapped inside a revolting wasteland,

red-white-and-blue, by a superfleshmetal nuclear blue Buick,

hurtling alone and out of control through a starry night,

about to blow his world into scraps of pasta and cheese

splattered by tomato paste, and scare him out of his skin.

Something was in the way. Was the old man calling his name,

or was he sleeping again?

I

have decided to write a sort of book, Rev, and to include

this dream in it somewhere, claiming it is the dream of a

character, a special character that I am inventing, named

‘mj’.

But

the truth is that I’m having dreams again. Chipewyan knows

this only too well, but with dreams about blue Buicks and

ravioli, I’m short on faith he can help me understand them.

His face appeared in front of mine again when I dreamt and

heard my name, and he frightened me more than he comforted

me this time.

Mortimer,

in the next section, seemingly the following day in

I’ve

decided

to continue with the book, Rev, and here is another piece of

it. I’m concocting a love affair between an occidental

doctor and an oriental Indian princess. (“Delkrayle;” Hindu

temples;

I’ll

start

it now and finish it in the spring and send it to you in

pieces to tickle you and keep you believing in something

when your life dries up like mine. If I wander into details

of sex and love, you won’t be angry, will you? Chipewyan’s

Indian legends are prodding my curiosity, and until spring

comes and I can move about again, I’ll have to be curious

with my mind and not my body.

On

the other hand, Chipewyan’s granddaughter, Dlune, came with

her mother to check on the old man. Mackenzie describes the

Chipewyan women as the most beautiful of all the northern

tribes, and I’m prepared to believe him. This one doesn’t

know it yet, but she’s going with me in the spring. She

doesn’t know she’s going to visit her grandfather and

me (and bring me a volume of Nietzsche from the Fort Smith

library), that she and I will make a tent and two knapsacks

and a double sleeping bag, that her mother will help with

this last if she wants her to, and that I’ll show her how to

use it, and she, me. She doesn’t know that we’ll be setting

out to conquer the Peace River country together and then the

But

that last idea strikes me as wrong, Rev, and I already know

that in this book of mine I am not going to follow

the

And

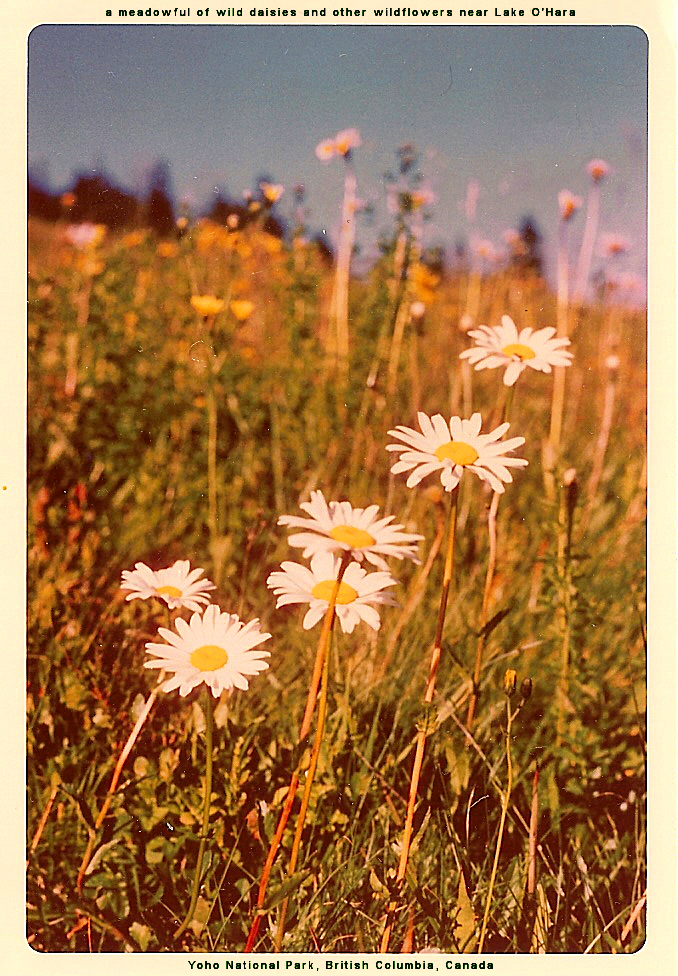

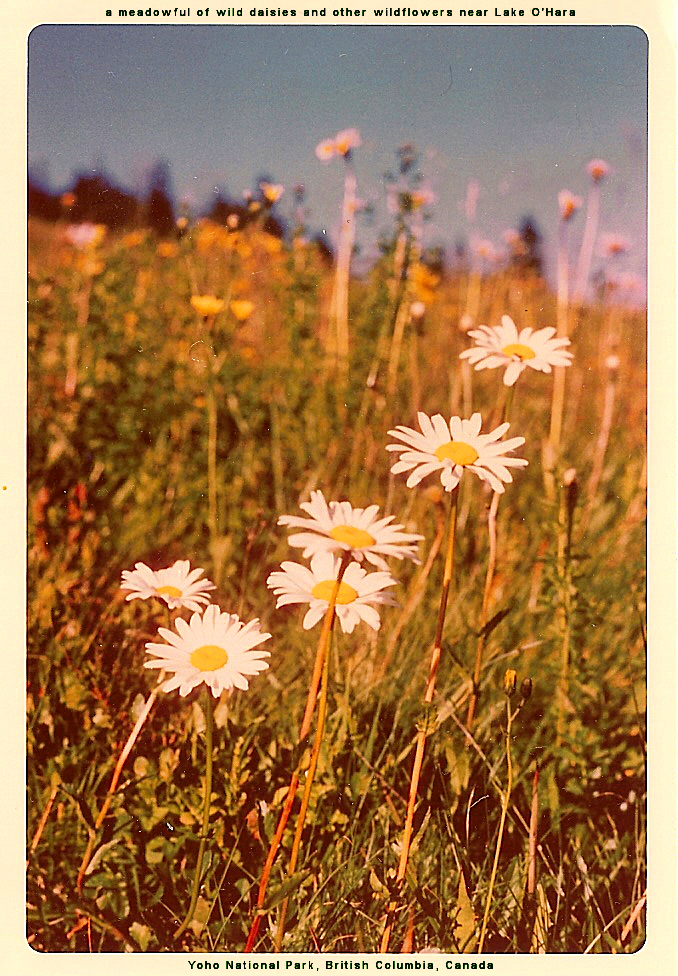

I will play in alpine meadows with this one. I’ll run in

them and flop exhausted on my side, my sad face turned

toward hers. And we will look down at our feet and count the

delicate petals of Arnica alpina. We will look together into

the hearts of Purple saxiphrage, and then will look into

each other’s eyes and know. Because my

And

avalanche lily. My reference does not include the avalanche

lily, but I know it and recall it from my trip up the

168. the Lorenzos were

overjoyed, but not for long

The

Lorenzos were elated

with this, for their son seemed healed!

But

the next little bit was a letdown, not surprisingly. Mortimer

did not explain his intention, because he wanted them to

figure it out. But they never did, quite. He wanted to show

that depression still knocked him off his feet like giant

ocean waves coming ashore, alternating with calmer, quieter

waves of relative contentment. He wanted everyone to know how

deadly and tenacious a depression was, how it fed on itself,

circling and circling in the same self-defeating thought

patterns again and again. And he hoped to present enough

detail of his own depersonalization and depression so that

others, once they had read his ‘book’, would recognize the

thing if it happened to them, and not make the same mistake he

had, of failing to identify it when it first struck him in

college, and letting it get the upper hand in that way. And

too, he wanted his parents to finally understand what in the world, exactly,

had made their son bolt from daily routine and live a crazy

and drastic year. The answer was: the ugly, ineradicable

mental illness described in the notebooks, the clinical

depression he had hidden from them for years.

Again

the pundits said Jack was operating behind the scenes here.

Quietly. Already three months before spring Break-Up. They

said it was Jack’s idea, not Mortimer’s, to have Mortimer look

at himself in the mirror of his med school diaries. ‘Mortimer’

was letting ‘Jack’ make more decisions like this, they said.

In any

case, though Mortimer might have felt and sounded a bit better

at times, he still suffered waves of terrible despondency and

wanted to show the

relentless, treatment-resistant, devastating depression, the

feeling of being barely a person, barely human even, caused

(according to Jack) by years of SOMEBODY’s terrific

totalitarian regime. And to convey it convincingly would

call for some detail.

There

was no need to write anything new though. The notebooks from

med school described how he felt on bad days now. And again,

as at the end of his ‘third attempt’, he tossed in a

representative few pages because a wave of depression was

knocking him off his feet right now, on the island in

Lake Athabasca just a stone’s throw from the little village of

Fort Chipewyan.

And

those passages knocked Rev and Jo off their feet. They

made very

unpleasant reading when coming on top of the interrupted

stories of Delkrayle and Dlune. Every single time the Lorenzos

floated away sweetly on a warm love story, they were

immediately mowed down by a freezing, breaking ocean wave of

depression. And they could not stand it at first. It was not like anything

they had ever read. And in fact, as far as they were

concerned, it was not like anything anyone should ever

have to read. Once a story began, especially a romance,

as Jo complained to Rev – day and night, in fact, for she had

read Love in the

Limberlost and many other lovely stories of love – it should continue

uninterrupted, or an audience would lose interest.

“Hasn’t

he ever read a love story?” Jo asked her husband. “He has to know better.”

And

Rev agreed.

And

the pundits too. For they too were terribly embarrassed at

times by the intrusion of Mortimer’s vomitously depressing

notebooks.

And

yes. He did ‘know better’, as Dr. Lorenzo explained to a

pundit audience once, years later. But Mortimer, though he

would spend the winter hiding from the truth about his reduced

role in the future mj, still sometimes was – and at the least

convenient times – exasperatingly committed to certain useful

aspects of the truth,

painful or not. And the sad truth was: he

suffered depression now in

So the

format continued, of bowling Rev and Jo over with wintry,

miserable notebook entries ‘every dang time',

as Rev said to Sammy later, 'that Jo and I began to

enjoy a little vacation of pleasant amour’.

And

so, the first wrecking ball of depression had to come crashing

in RIGHT NOW, right on

top of all the delightful spring alpine wildflowers.

169. the whole world

condemned Mortimer’s new ‘roller coaster’ writing technique

No one

could say there was not mad-ness

in the method, argued pundits facetiously. But they

argued uselessly. For, nobody in the whole world

ever came around to really liking this ‘mad’ trick of Mortimer’s, even with

all the pundits’ joking and theological ‘apologizing’ for it.

Many readers skipped the depressive notebook passages wherever

they turned up. And the pundits hated the passages too, it was

true. Mortimer’s depressing notebooks embarrassed the pundits

to tears many times over the years.

But,

said the very same pundits, anyone who skipped those passages

ran the risk of not grasping sufficiently the nuts and

bolts of the driving force behind the making of The

Remaking, i.e., Mortimer Lorenzo’s grave ten-year-long

depression during his young-adult years.

I

reach a point where I am unable to think at all. I can

only sit in bed and vegetate. I am also emotionless.

I

know that writing this is becoming navel-contemplative,

but it may help. I know that I am ill but am too weak to

heal myself. I pout inwardly: why this, and why that, I

ask. And how I loathe myself and my state of affairs and

how can things get better.

Possibly

the most interesting fact is that my desire to do anything

to change is remote. I excuse its distance with thoughts

of more pressing thoughts. This in itself produces

despair, when I realize that any experience of the Good

must be suspended until later. I conclude that everything

must remain the way it is. I have to keep trying to

understand myself or I will be out of my room on my ear

and then up to my ears in the warring world. That which I

think I want to do most of all, which is to live,

must be suspended.

But

is it not possible to live now, even in the height of

devotion to writing my thought? Perhaps, for example, this

depression or despair is only a habit, a bad habit, and

there is no actual ground for despair at the moment. Why:

in fact, this is what I find, and this is what increases

my despair. My depression comes to my awareness and that

depresses me, for I see it as uncontrollable. I do not

think of it objectively or analytically, saying, “How

interesting. As I sit here I find myself despairing. Isn’t

it interesting that I am human and can act and despair at

the same time?” On the contrary, despair impedes action

and I vegetate in helplessness. Woe is me. I pity myself.

Perhaps

what I should say is that I do not accept despair. Of

course I realize I am only repeating the other statement:

“I despair over my despair.” The point that I am making

this time is that I do not accept myself. To

despair is not sufficient cause for alarm. But to despair

of ever being able not to despair is worse. It is

not accepting the original despair with a grain of salt.

It

is at this early stage of despair that I can catch myself

by the tail, saying: “As I sat here a moment ago I

suddenly felt ashamed of myself for writing all that

Kierkegaard clarified 100 years ago so cleverly and

persuasively, and that I apparently failed to incorporate

when I read it:

At

the second and theoretical succeeding stages of despair I

cannot catch myself and have no desire to or hope to; my

thoughts go something like this, with a mental grown and a

pout: ‘When will I ever learn to accept myself as the dunce

that I am? When will I ever get out of this terrible state of

nothingness in which I hate myself and everything? Oh, how I

hate myself for even saying this!’1

And

here is the greatest blow of all! As I lie here in fact

literally at this moment, not necessarily do I, having

made these observations and analyzed myself presumably

correctly, not necessarily do I even feel like

inaugurating any movement for reform. This is after all my

thinking, which did itself come with difficulty, be sure;

for I began trying to think yesterday, even last week or

last year, with limited understanding. Situations such as

this encourage my belief in fate and the uncontrollable

mood. “For some reason or other,” I am in the habit of

saying, “I feel better today,” or “worse,” as the case may

be. I habitually accept moods as inevitable and only

conquerable with the greatest difficulty, if at all.

170. Mortimer pushes

his ‘roller coaster’ technique on his readers

Lest

the Lorenzos get too terribly depressed, Mortimer – quick! – zapped them

with an upper as promised. And he continued to hound them with

this mind-bending, gut-wrenching format for the rest of the

‘fourth attempt’:

Here

is the first installment of the love affair I am concocting

for my Book. And I force myself to this endeavor, Rev,

because I realize that I must learn to write plot-fiction first and

other things after. It is all that people will read without

complaining, really. One day, I think, even before I die, it

may be the only way left to communicate in writing. College

texts may be replaced with historical, sociological,

psychological, religious, etc., novels, because

students will not, will simply not, will be unable to, read

pages one through twenty-eight (my age and Mackenzie’s his

winter here, roughly), unless the word is out that shortly

after page twenty-nine will come an encounter between the

sexes to beat all encounters, and that the suspense,

moreover, will not climax but only begin there.

I

have to be able to construct an ordinary story line with suspense.

So

there they were, our friends, Delkrayle and the Western

doctor, of opposite worlds if ever there were two such

worlds. But there I go again, interpreting the book before I

write it.

I

am going to continue referring to the doctor as ‘mj’, so

that you may be sure that it is not myself that I am writing

about, since that is a booby-trap for starting authors.

Delkrayle

was

the pretty name attached to the younger of two daughters of

an Indian raj or prince-king-ruler in the state of (???),

close to

But as for Delkrayle growing

up: because the British and Irish or French – who can count

all the restless European peoples? – came to take advantage

of the defenseless Indian subcontinent and dominate it, her

parents sent her to a Catholic school. But they and she were

Hindu. Then how could she have syncretized the sexually

uptight nuns in their body-erasing floor-length habits, with

the delightfully twisted, love-making postures of carved,

naked, phallus-aroused gods and nipple-erect goddesses in

all those temples that were meant to inspire an Indian girl

to worship her Indian understanding of The Creator,

that super-sexy, forever-dancing, constantly-meditating,

perfectly energy-balanced and nervous-system-focused – brain

to bum – Creator?2

Or did she become a lovely lively unresolved duality? No,

the Indian way superseded, I think. And so, in ‘66, with

that sensuous-spiritual, very-Indian unity-of-life pumping

in her veins, she stepped out the door of the plane at

I’ll

defer

telling you about ‘mj’ until the next episode. He’s the less

alive and convincing of the two, so I should paint him in

more detail, and that will require patience. But what could

we have expected of this death-ridden one, this would-be

medicine man from that up-to-date country, that

whole-planet-dominating country, that Christian

Western-world country, about to clash head-on with

Delkrayle, the fragile and beautiful, sensuous yet elegant,

end-of-the-line oriental quasi-princess?

And there were more thrills before

the next icy water-dunking:

Was

Delkrayle, then, as acknowledged as she deserved to be,

whenever she walked the crowded dusty streets of her city in

those rare and costly, obviously-princess, gorgeous silk

sari’s? Yes; and not unlike a movie star; but safe from

sidewalk stampedes. And was she beautiful? Like the morning

star, indeed; and far, far more than her sister; and

surprisingly, if one met her parents. And intelligent she

was as well, yet not a little spoiled because, I regret

saying, she knew every bit of this all too well. She knew it

because at the age of five she had been carefully ‘engaged’

by her family, in cahoots with the (family and)

king-raj-ruler-would-be-quasi-ex-potentate of another

neighboring ex- and vanishing Indian ‘state’, to some day

marry his son and shining prince. And with this prince,

Delkrayle had even taken painful care to become exceeding good and natural

friends. And with the memory of this dusty, bejeweled

fairy tale inside her, it had to be: she stepped off the

last aluminum rung of the airline loading gate onto United

States and very material – and (Lord!) oh so costly to

spirit – New-York-Brooklyn real estate.

I should add here that

Delkrayle was no stranger to the Western world, either,

since she had spent the summers of childhood along with her

parents in a European capital, during the years when her

father had been an Indian sub-ambassador. Then could she

have met the soon-to-be late John Kennedy when his father

was

And

I like the idea, too, because it helps explain why Delkrayle

chose a JFK pet project like the Peace Corps and stopped for

awhile in the mountains near mj and Philadelphia, at the

India-Peace-Corps Training Camp in the Poconos.

When

Delkrayle

walked, her beauty was absolutely unmarred, for that was the

nature of the beauty of the Indian sari. Her body was

undivided. It walked entire upon the sidewalk, top to bottom

a single harmonious willowy unit, not a seeming top and

bottom, not a sequence of head, neck, breasts, waist, hips,

legs, and feet, in that and no other order, but a single

sensuous field of magnetic resonance there moving, waiting,

attracting, responding in unison, wanting to be met and

touched and felt. Thus to touch a passing part of

Delkrayle’s silk costume was to feel the most intimate part

of herself, not because she was totally shielded, but

because she was totally open and whole.

But

I have to summon reality now to show me this Indian

princess. For she was undoubtedly spoiled. She knew her

special-ness. She was aware of herself. And therefore she was lonely.

And occasionally she was nasty too. But it is hard to

remember such times, I admit, and difficult to imagine them.

Let us say, then, that she was at times too easily hurt,

that unless attention was channeled to singling her out and

inviting her to enjoy a night on the town with the Peace

Corps trainees she would not simply get up and happily go.

Her defense should have been that she expected a special

invitation because she was a princess. But since she had

revealed that fact to no one yet she was deprived of that excuse for

feeling slighted. Should anyone criticize her mood, or her

gilded sari silk, she was left to refer to the fact of her

family’s wealth, while selfishly harboring the secret

fantasy of a would-be prince

within her. She would try to remain alone and aloof, and to

that extent, self-centered. And then she would look for

something to knock her off-center. She would love to lose

her balance and fall, would like to love. She would like to

try a volunteer from

171. the Lorenzos are

ecstatic

The

Lorenzos were swept away! They could not have been more

charmed and seduced, for there was romance! And

better yet, a sensuous atmosphere of impending sex! And they

liked sex, after

all. Who would not?! But only in secret and in private because

they considered it bad taste and un-Christ-like to reveal or ‘advertise’, to use

their word, that

they liked it. And their son’s way of referring to that politically

super-sensitive area, for a Calvinist-Methodist preacher’s

family, remained discreet and acceptable in this case, for

once. ‘ALMOST’, as

they always qualified, by which they meant, obviously, ‘almost except

for the carved stone erections’. Yet it was all

surprisingly sensuous ‘SOMEHOW’,

as they put it, by which they meant ‘even with those dang

unmentionable carved stone things’.

How

had he succeeded in seducing them? They could not have said

aloud what they were feeling, ever: that he had used the

aroused stone gods and goddesses to get his sexy

point across without offending them.

Yet –

however he had done it – he was not supposed to have been capable of

anything close to it, if you asked them. First of all, he had

grown up with them,

a smiling, delighted little Christian boy. That alone

should have stopped him from implying sensuous sex in a book.

Secondly, everything at

Dr.

Lorenzo said years later that when he first read this

description of his parents as prepared for Sammy’s 1980 ‘first

revision’ of The

Remaking, and realized Sammy would not have made up

anything about ‘young mj’s beloved and respected parents’ –

for Sammy actually liked the Lorenzos a lot (and they were

very fond of him too, at least as much) – he laughed himself

sick for a month, actually giving way to tears at points.

Because when Sammy conducted the interviews in 1980, Rev was

already 75 and Jo 70, and no one could say how long they would

be around, doing and saying their usual funny things.

172. Dr. Lorenzo

explains how Mortimer ‘got away with it’

And

the Dr. swore that as soon as he had a minute’s time he would

share with

A

statue of two aroused white youths, therefore, naked and

modeled on a known young white couple from Florence, N.J.,

could never, ever, have done anything but trigger the by

now virtually genetically-endowed ‘haunt reflex’, or ‘startle

reflex’, possessed by certain funny kinds of censorious,

sex-condemning Americans, obviously. While a statue of two

aroused Mexicans, on the other hand, a swarthy young man and

woman with Aztec facial and body features, might actually have

passed censors of the ilk of the Lorenzos, especially if the

young man had worn a big neck chain with obvious medallion of

the Virgin of Guadalupe, distancing himself even further from

people like the Lorenzos. But not, of course, if the statue

were ‘erected’ in

Dr.

Lorenzo could go on for hours on the theme, actually, icing

the cake thickly the whole time with double entendres. And he

did in fact present on one occasion a fall-on-the-floor funny

‘lecture’ on the subject at

173. the Lorenzos

accept punishment for so much questionable fun

Anyway…

the Lorenzos were surprisingly won over by the story of

‘Delkrayle’. And fascinated, too, to get the details, they

assumed, of the affair their son must have had with ‘that

Indian girl in the sari’ he had brought elegantly sidesaddle

on his Honda 50 all the way across the Ben Franklin Bridge and

up Route 130 to Florence that one unusual day several years

ago. It was best – though sad – that a relationship ‘like

that’ had broken up fast.

But they were thrilled with the writing, so thrilled they

bowed their heads to accept their deserved and allotted, even

scheduled punishment

of depression, ‘like an old married couple running

for joint papal sanctification’, as Rev said drily.6

The promised dose of misery was all the more warranted now,

though, in all seriousness. For they knew that they were not supposed to

have enjoyed ‘risqué sex’ that much, least

of all in a son, and even less in front of each other.

So Mortimer’s perfectly designed, scheduled punishment for

them had to come swiftly, of course. He knew, apparently, that

they would need it quick!

Before they could ever go on and enjoy any more such chaff. And more such ‘chaff’ he

did indeed have in store.

The

notebook entry chosen as punishment described once again the

depression which had plagued mj lorenzo since early college.

It showed he suffered from two things, (1) an ongoing and

seemingly unavoidable overdose

of protracted formal higher education due to a feeling that he

had to do what was expected, including at times even his

perceived mission of saving the world by writing; and (2) an under-dose of real

get-down, earthy, natural, simple human life; that is, love,

friendship, and natural, friendly, flowing, lovely

relationship of every natural human kind. And it showed the

depression, depersonalization and dehumanization that had

resulted from all of

that.

Despite

any contrary appearance, I experience life as a lack, as

something incomplete. I am not content. One could hardly

say that I am happy although I am not at the moment seriously

depressed and have given up my bitter passing comments to

contemporaries.

Each

moment is experienced as a deficiency of something, a

premonition that something is wrong and may never be

right. Each event that fills time, one upon the other, I

realize is slightly pointless. My friend comes to my room

and I attempt to make conversation. This is in order that

everything will not collapse about me. My natural tendency

would be to hurt him, to annoy him by being no fun

whatever. I feel that our conversation is not complete and

justifiable in itself. Why have we done it? Why am I

talking about what does not interest me?

I

am slightly uneasy, slightly tense. My mind is not fully

given to this conversation, although it’s not busily

occupied anywhere. It is diverted into the channels of a

vague anxiousness, and only a part of it remains for

handling passing circumstances such as friends. Being too

conscious of its activity it does the activity only

haphazardly, half-heartedly, awkwardly. The rest of it is

grieving vaguely over its own almost-death.

The

windblown cold falling snow outside my window does not

belong with the boisterous screaming music that comes

through my walls from the radio, or with the voice of

someone next door nasalizing with it. Planes droning

overhead confess to me that their white snow world is not

pristine. It is not the soft mother we might want. A white

snow-laden steeple-punctuated dorf7 in central

There

are always those things I cannot express, these things.

They line up and stand between the outside world and me in

the form of a wall. I give them a sign of recognition,

tolerate their standing there, but they do not go away,

and each time I try to pass around or through them I feel

my efforts falling back. Enough of my striving gets

through to people that my isolation is not disclosed

acutely, or therefore, painfully. Only an astute person,

one who has experienced what I have, may realize. Others

will draw their conclusion: he is a quiet person; he could

not hurt anyone; he seems to think a lot.

While

all of this is taking place, I am holding something else

back. I have not tried to dig it out, but I feel that it

is there. For as I now re-read the above, I begin to feel

a certain wasted-ness. I do not feel it passionately. I

have played the tape backward, and transferred to paper

the thoughts of three days. But where am I? I am not in

those thoughts. I am a machine that has operated at given

hours and tried to give the proper answers on request. I

will never go berserk; I will always do my duty. I am

fairly predictable, for I conceal my unpredictability. And

I lack passion, am uninteresting, and a bore.

But

this is all a part of my relentless illness. One day soon

I will have to stop writing and resume my professional

martyrdom. I chose a half-unwanted vocation and am caught

in the contradiction which resulted. I shall go to sleep

late and rise early. The ringing alarm… I will not want to

get up on that day, but I shall pretend to want to. As I

close the door behind me I shall secretly rejoice that I

have beaten half the world to work. Being a doctor must

not be a bad job, after all, I shall think. It’s better

than suicide probably, and it gives me a head start on the

rest of the world in the morning. I can suffer the

drudgery of learning to listen to hearts and look into

eyes, and allow it to fill up begrudged afternoons.

But

I shall not be able to defend one single thing that I do.

I will merely act now, and disparagingly, in the

half-hearted hope that later an explanation might arise.

My faith is in myself, my future self.

I

might even believe as well in my present self, its

capability of bringing me to a later resolution, or

directing me towards it at least. I will grant it its

difficulties, having as it does a limited time in which to

work. Its time has been sacrificed to a medical vocation,

perhaps itself a waste of time, but an investment on which

I cannot bear to lose the down payment, for I am afraid it

would be a mistake of equal size to that of having made

the down payment to start with. I simply do not know. I

feel that I do not know, cannot understand, can

not resolve these thoughts. And right now I

dispassionately do not care.

Meanwhile I go on. I do

not bathe myself tonight because I did so this morning. I

shall study medicine a bit more in order that the day may

have been balanced. Too much dreaming and not enough work

may be embarrassing later. How do I accept all of this?

How can I endure it? Mountains are gleaming in the

distance. Tiny villages are peaceful in

Baden-Württemberg.7

A hundred thousand peasants here and there all feel their

life is right. I feel that I have been born to a life that

is wrong, which I must bear, either temporarily or

permanently. I feel that to happily enjoy a fine mountain

or a small town will be a deception of my self, an escape

from the matters that must be settled before I may enjoy

life peaceably. But I fear that the matters may never be

settled and that beauty, instead of making me happy, will

make me angry as it conspires to tantalize me. Does it

want me to believe that the world’s, or my, life may be,

like itself, beautiful? Have my happy moments not been

mere escapes from a fundamental anger?

'The

doctor is well aware that the patient needs an island and

would be lost without it'.

C. G. Jung8

I do not know

whether to attempt to be “normal” or to resign myself to

eccentricity. Perhaps it is wanting both that causes the

cleft. I totter daily, momentarily. I am one on the

outside and the other, in; I have sought to model the

inside on the outside. If the outside slipped toward

inside-like-ness, I sought further outside myself for the

tiny 'island' 8

of remaining sense on which I could found my outward

behavior; and started over. At times I was closer to

wandering onto the ice and dropping in.

Hell

may be like this.

And then, as his new roller coaster

technique required, Mortimer returned to his ‘new book’

without warning.

Mj

was no lady-killer. He was a would-be lady-killer, however,

just emerging from the pages of his Old Testament,

textbooks, and Kierkegaard, who from reading and watching

television had learned to smile and act like one. He was a

fake, trying to require that a dream become real, but having

to accept – yet could he? – an interim substitute in the

shape of a daydream. But in truth he was less and less

content with such a solution and wanted to explore the

waking world. Delkrayle was his second attempt at a love.

The first was her everyday stateside roommate.

It was mj, visiting the

Pocono Peace Corps camp,9

who sensed the pique of the rejected princess in Delkrayle

and persuaded her to go to the movies. He insisted that he

would buy her fancy ice cream. It didn’t matter if ‘they’

wanted her with them or not. He did. That mattered. He

wanted her with him. He was growing intense. He was about to

detect that he might care, or rather not to detect at all,

but only to act as if he cared somewhat, discovering it only

later back at school when she was still at the Indian Summer

green and yellow mountain camp of cool fresh weekend air,

lake, and woods, and all that Philadelphia and he could not

be, on a hot humid pharmacology-lab Indian Summer day,

realizing that he did care.

Delkrayle

(pouting):

I won’t go on their silly outing, the silly Americans.

Mj

(would-be lady-killer, smiling): Why won’t you come? Come be

with me, then. I’ll buy you ice cream afterward.

Delkrayle: I don’t want to

see “The Pawnbroker,”10

misery and hate. I’d rather stay here by myself and think,

for a change, in peace.

Mj

(the doctor): You know, Delkrayle, it seems to me you’re

hurt about something.

Delkrayle

(silent…

a look of… embarrassed exposure, as her eyes meet for the

first time his; not with love; yet): What makes you say

that?

Mj

(acting himself for once, stumbling into a confession): At

meals, and around the camp. I can’t keep my eyes off your

beautiful sari [your

beautiful you] and long dark hair. I want to touch it.

How about if we both stay here and talk?

Delkrayle

(rebounding):

That’s all-right. You can come to my room if you like and

look at some pictures of my family. (She was homesick and

thinking of

Mj

(the doctor-suitor blissfully trailing the Florentine

lady-patient to her boudoir, dizzy from mystery, not

subjection; but where was the mystery in a few photographs,

a sari, long dark hair, and an Indian-British accent, when

medical school left hardly a minute to discover it?)

Delkrayle

(in

her room, which was her roommate’s as well, overlooking the

lake and campgrounds from the second story, she suddenly

found herself with nothing to say; flushed and embarrassed,

in her room, with a strange foreigner she had too carefully

watched since his first weekend visit to the camp, she

located the photographs and sat down next to him on the

bed): These are my parents.

Mj

(her roommate had kindly ‘warned’ him that Delkrayle was a

‘trickstress’; did her parents’ eyes reveal it? Here was her

sister, less attractive. The subcontinent was throbbing with

dusty life. He wanted to study maps, climb to hill stations

in the sun, attend her family’s parties. He would sink into

the Indian way of life like Siddhartha in the

I

don’t know where to take them from this point.

I

know that mj would have dropped the subject in order to keep

his visit simple. More than likely they talked about

Altogether

the

meeting must have ended indecisively, and today I am trying

to discover what happened. Where did the Western-world

doctor go once he reached the room? His spirit and will must

have flown out the window and drowned in the lake, following

a few practiced moments of doctor’s concern for her mood. It

appears he was suspicious of something or other, but I have

yet to learn of what.

Plus the due punishment:

What

is the smile?

I

realize the smile is not mine. It glowed ten blocks on

West Philly’s

What

is the feeling of disjunction, the feeling that my flesh

is pale, my face is young, and I am being seen but

discounted? Yet: the look of composure, the look of

innocence when passing near without a word, concealing a

rapid pulse and a frightened brain. The stiffness in a

neck, if it were studied at such a moment, would reveal

that there is not innocence, but fear. And guilt.

What

is the disjunction when I wave and smile? I know that she

might as well be dead, or an

The

city looks like the pieces left by disaster, dropped back

into rows somehow, but the parts still out of place.

Railroad bridges full with working trains canopy the main

street. Georgian massive Provident Mutual is dropped in

the heart of slum. The sidewalks of

If

the storm is over, then why is the city pavement full of

trash? Are they the small pieces that could not fit, that

cover the ground? Have the clouds married the sun and

dropped confetti? Or is it the end of civilization, the

rear end, sitting in motionless distress. Indisposed.

What

is the disjunction of wanting but fearing, wanting but

fearing… each thing, each person; each action: torn by

this. What is the disjunction… between the idea and the

actuality, between the emotion and the response…?

The

smile is the brief finger-hold on reality. The disjunction

is the need for this, just this, as you compare this with

all the rest. This is the disjunction.

And then again more ‘book’, and so

on….:

What

Delkrayle

surely knew but did not hint that she was troubled by, was

that mj was seeing her roommate. What mj knew but never

admitted to her or himself that he was troubled by, was that

Delkrayle knew, but never hinted that she was bothered by,

the fact that he was seeing her roommate; that he had come

that weekend to see her roommate, but the reason he was free

now was that her roommate was tied up in a meeting; and that

he was obviously torn between his feelings for her… and for

her; that that

was why his mind had wandered and disappeared for whole

parts of minutes at a time; and that – probably – he should

have liked it to remain this way so he would never need to

make a commitment either way.

But

on the contrary if he could have pulled these two into one,

he might have been ecstatic with the solution. One was the

logical sensible prosaic arrangement for him, the other an

absolute dream. One was a little too easy for him, the other

was much too hard. One went beseeching to his feet, the

other rushed to his head. This was one situation where

Kierkegaard’s ‘Either/Or’

could not apply. He wanted both. One would serve him. The

other he would serve like a pageboy. And who would not serve

a princess?

Did

he serve her then, when her roommate went back to her home

near the western mountains and he found himself on his way

to see Delkrayle finally this time with no complication? Did

he serve her whenever he tried to steer the car and she

grabbed him around his waist and bit his ear? Did he serve

her whenever she praised him for this or that, or built him

up to be (only possibly) broken down later, or flattered him

in order to (also only possibly) hurt him later, and slowly

collected her overpowering world around him only to…

Then

why did he suspect that he had only served her? I suppose

for the reason… that he had.

…………………………

Even

though, Rev, I may have left the impression that I am

spending the winter with Chipewyan, in truth I’m spending it

with myself. There are places in the cabin where I can get

away from him and thoughts of him and from everything. There

is an extra room with a bed where I can read the notebooks

and conjure my fantasies. Sometimes I retreat in my mind to

the outhouse. Sometimes I walk outside, not knowing for sure

where the island stops and the ice begins. But it’s all the

same, a pristine cold glassy whiteness, diffusely reflected,

and I am alone. I can cut myself holes in the ice and fish

for food. I can check the nearby traps, and I do so

mechanically on periodic trance-like trips in all

directions.

For

the longer lines I need a backpack, several days, and a

vague sense of the terrain and of who might befriend me on

the way. And on one of these trips through the woods I have

come to

Girl,

I will check my lines more often. I will fit you into them

whenever I can. I will cross and realign the route so that

you are at every paltry junction, at the end of every

semi-dark day. So that you can help me by removing my

snowshoes and heavy parka, for which I have temporarily

traded in my sleeping bag, so that in time I can reverse the

interchange, inviting you to share my special sleeping bag

with me. Will you like it, girl? Will you come as easily to

that world as I go to yours? Where do you attend school? How

do you live your afternoons? How did you learn to make

breakfast like that?

…………………………………………….

My

mind is compressed, my shoulders stiffly strained, and my

face hides a pained frown beneath a Mona-Lisa-like

peacefulness. As I sit apparently comfortable, I am

un-relaxed, respiring rapidly. My mind writhes, but not

this time in the centers of intellect. Somewhere beneath

the conscious cortex is a mass of currents seething in

their efforts to get out. “In which way is this energy to

be turned?”

A

hundred thoughts pass. I can sense them turning just

beneath my conscious surface. Many thoughts on many

subjects, both sides of many arguments fight for the

single pathway to daylight. But I, myself, whether

controllably or uncontrollably I cannot tell: I am not

letting any one win.

Where

does the capacity to write and think like this come from?

For, as it proceeds, it senses that something beneath it

far more powerful and important is about to depart the

womb, rupture into life and be born.

How

is it possible to feel like dying, to be aware of it, to

not wish otherwise, to not have energy to alter it? White

walls, bland radio music, gray dusty world of things and

people. Not a spark. No hope.

Sweaty

pits, greasy hair, an eyelash irritating my sclera, unable

to remove it as long as I am writing, I drool.

The

perfect act goes on and no one knows the actor is dead.

I

hold my eyes open and no one around me suspects…. …except my hired

friend.

………………………………………………………….

I

can see, Rev, that I am going to discover that this Dlune is

a princess; because her father was a chief. The one whom I

will have treated like a slave, and who will have served me

ably as a slave (she is in fact half Slave

tribe and half Hare-Chipewyan, but was raised in a Blackfoot

tribe), is really anything but a slave, though she will wait

a long while before telling me that. Why: because it is only

important to her for the moment to serve me? No, for that

will make her unattractive. Because, among the Indians there

is no honor in being a Slave chief’s daughter? No. That’s a

self-deception. Because, she knows I am not ready to handle

her as a princess, that were I to know, I should explode and

lose my way, that I would flounder without my supposed

superiority, and that only in time would all of this be not

so, in order that I could more gradually adjust to the

painful duality which she represents and truly is, a duality

I could not accept until I had accepted the duality of

myself….?! Yes. That’s getting really close.”

Dlune:

Mj,

I’m a princess. (Mj has been telling about Delkrayle.)

Mj:

I know, baby, you are a princess, thanks, I don’t know what

I’d do if you weren’t. How could I enjoy the flowers without

you? How could I even sleep without you? And why else would

I feel so much like a prince?

Dlune:

Mj,

won’t you slap the mosquito on my back? Here, did you want

peanut butter or cheese in your sandwich? Mj, I don’t know

how this might strike you, but: I AM a princess.

Mj:

Peanut butter. (‘slap’; a long pause; and less dramatically)

I know. Your father was a Slave chief.

Dlune:

Oh,

mj! I knew you were ready for the truth. Now I’m happy.

(cries)

Mj:

Really, baby, it doesn’t matter any more. Don’t cry. Here’s

the wrapper. In a setting like this big things suddenly

become small – the olives are rolling for the cliff, Dlune –

and small things big. You got ‘em…

Pause.

Both breathe heavily following rescue of the olives. And

they think while taking in the setting, which consists of a

grassy alpine meadow of about thirteen acres, surrounded on

three sides by high rising cliffs, while the fourth drops

steeply to the

Within

barely

twenty yards of them amble a family of elk, and further away

in all directions are grazing elk and buffalo, many with

young. A spectacular spring waterfall pours over the rear

cliff, and its stream bubbles twenty yards from them in

another direction. Flowers speckle the lawn and tickle their

picnicking calves. The sky is blue with a yellow sun, and

Dlune is wearing a green, yellow and blue cotton dress and a

matching Indian bead necklace touched with red. Her hair is

lazy and black and her face is beginning to assume the

dignity of an Indian princess.

Mj

(interrupting the silence of the waters): Dlune. Let’s study

the flowers.

There

is commotion in the grass which the animals accept. They

can’t miss the ensuing nude dash of two brown bodies toward

the plunging waterfall and into it or the shrieks that

accompany all this. And in time they are left alone again to

contemplate the flowery peace.

…………………………..

A ‘crisis theology’ is a

system of thought designed to deal with critical events in

men’s lives, not with everyday situations. That is how I

like to use the term anyway. I believe Reinhold Niebuhr

first invented the term to describe Karl Barth’s theology,

which may have been, they said, well suited for unusual

times like wars and revolutions but was insufficient for

guiding everyday men.11

And

I have discovered another type of ‘crisis theology’

related to this one. It belongs to the type of person who

can deal with people only when they are under stress and

in need of help. It knows how to stoop the knee and bow

the pitying head, shaped in profound understanding. “The

Rock during times of crisis,” it is called. In reality,

however, it is inability to react emotionally to great

human need. It is lack of compassion, lack of a sense of

what being daily human means. How is it that people will

seem to appreciate the act nevertheless? Could they not

sense the separation, the schism between the real and the

unreal, the natural and the unnatural, the felt and the

thought?

A

person with such a theology may want to become a priest or

preacher, or even a revolutionary. He may feel his calling

to bow the pitying frame and stretch the soothing hand. He

is well suited for baptizing; and for blessing marriages,

for raising the benedictory palm, for Sunday mornings

thumping the pulpit with clenched fist and later at the

door shaking everyman’s outstretched hand. His theology

and politics contain concise interpretations of all

imaginable crises, to the last detail of which he must

faithfully adhere, remaining therefore at peace and

emotionally vapid during these great, or potentially

great, moments in his and his people’s lives. And his

feigned emotion will forever be an act of generosity.

Wanting

to be a doctor at all betrays a ‘crisis theology’, but

wanting to be a psychiatrist especially, as I do… Could it

mean that? Able to sympathize with only (mental)

‘disease’. Not able to enjoy a healthy natural

give-and-take with others, or to touch their flesh and

help it live, or to make fleeting acquaintances

pleasurably. To require longstanding relations, chronic

pre-planned crisis, the distance of a desk between, the

contact of minds and not bodies…. Are these not symptoms

in themselves? What is that restlessness I feel when I

think of those in this profession?

I

fear a kind of ‘crisis stagnation’. I have seen mistaken

ways and views and the unhappiness about them. I have

suspected a tendency to perpetuate, to languish, and to

not think or ask, and most of all, to not do.

……………………………………………

I

have also learned to reason as follows, Rev: I have

exchanged my sleeping bag for a parka and bed. If Dlune

helps me off with my parka and into my bed, then won’t I in

turn want to help her off with her parka and into my bed?

Thus my words of deduction must bring me face to face with a

fleshy truth: that to be loved is still not so great XX#!%X

as to love.”

……………………………………………

I

am not going to the discourse with my confessor-friend. I

am sitting in the big bed in my room, my denuded room. For

yesterday I became resolute, tore myself from my bed, and

ripped the silly maps of North America down from the

walls, threw the three scenes of Canada’s Rockies in their

box, and hid a dozen of my most disgusting books in the

closet. I even used some old Bibles and Sartre to prop up

the center of my sagging mattress from below. In short, I

executed a mild revolution. Such a revolution is

superficial, but it may offer me a chance to think

clearly. These books and maps and pictures exercise subtle

controls on our lives. They hang over our heads and sit

looking at our waists and demand that we remember the

past. Our rooms become places in which it is only

appropriate to read and re-read the same old books.

I need to be reminded of

the present, not the past or future. I have been living in

past and future tense for a revolting lifetime. Notice,

too, that the past and future were always absent

geographically: they were in

But

the present may also be empty, as I’ve tried to explain.

For instance: I stated that leaving the room would not

return me to reality, any more than being here could

require my separation from it. Because, if I leave the

room and step into the hard cold concrete world, don’t I

take my room with me, with its four walls and their maps,

pictures, and shelves? And as I follow my usual route,

don’t they trail along with me on all four sides with

floor and ceiling? And as I tour the white

sterile-hospital world and even speak to a “friend” or

two, are the walls not there with their fears, wishes, and

memories, as if I were a patient being wheeled on a litter

under light anesthesia, and the “friend” was a narcotic

specter who pierced my walls and left me, unnoticed? Or he

may have thought that I was the specter; for, as he is now

deciding, he was touched by nothing.

Ha-ha!

There go I with my four-walled room, bed, books, garbage

and Canadian maps enclosed, like a surrealistic circus

through the snow. Can you see what all this hides as I

clown by? Does the masked expression on my face describe

the box I am in, the flat walls you can only see if you

study me? Can you sense that I am even short of breath

from the weight, the stiffness and stuffiness; that it

presses in on me with physical force until I frown and

frustrate? Now do you understand why I am nervous to the

breaking point and must return to my room in a panic to

catch my breath? How can I get out? Do you think that at a

time like this I can concentrate on the hospital or on the

lofty ideals proposed in a discourse? What appeal could

scientific and religious maxims, lost in their matrix of

past and future and book-bound fantasy, have for me now? I

am not rejecting them intellectually. I am just despising

them in my heart. For now I prefer my little stage

cubicle. Even though it is not entirely unreal, it is less

real than human people. It is even less real than God. But

it is more real than any maxim. And for the time being I

and my box prefer to perpetuate this condition. I can

flatter myself more easily this way.

Now

can you see why I have cleaned my walls bare? All that

remains on them are shadow silhouettes of goose-neck lamps

and bottles, and an extension cord dangling from the

room’s only outlet in the ceiling. You don’t think I can

fashion a pantomime from electric cords, whiskey bottles,

and stark goose-neck lamps!

Watch out!

But it was a

desperate futile gesture, this surgical debriding of my

room.13

I

am angry because I can not focus Jesus Christ onto this

moment. Besides, if I should try, I might succeed to my

humiliation. I was taught once that at a time like this he

cannot help except in the form of a flesh-and-blood

person. You won’t try to tell me that the form of his

human person nineteen hundred and thirty seven years ago

could break down my walls now. And either that

teacher was wrong, or I am triumphant, for there is no

person in here now but myself, and that finally settles my

claim that I am utterly alone…. most of the time.

Can

you imagine how I should communicate? I feel that no one

respects this world of mine or divines its peculiarity. I

am unusual! I can empathize with the esoteric writers of

my day! Is my every day not esoteric? I despise my peers

and teachers, their books and the outlines of their

habitat, as mundane and un-savable. I want to owe my time

to myself-in-my-room: my room, my box, my cubicle. Here,

where I can think and be alone, all alone. Here where I

can create life, manipulate it, describe it, and interpret

it. I can lie on my bed and deplore it. I love this. I

love the pain in this life, the colorless pain that

reminds me I am barely alive. I love the new barrenness of

the walls. I love the emptiness outside the window. I hate

the world, and here is where I can hate it best. Here is

where I have the time to ponder it. I love it! I love to

hate the world. I like to think of the pain of my poor

communication and communicate it. This is my life. I may

make it impossible to understand, and that may comfort me.

How

can I ever leave this room again and reach out? Don’t they

understand that I, I have become a reclusive

self-disguised Artist? I can communicate only from here in

my room. My excuse for not communicating outside

is that such is not my taste or talent. I am not adept at

describing or altering the progress of winter or the

smoggy outline of

174. and at the end of

the wildly up and down ride the biggest shock of all

From

the bed of: DR.

M. J. LORENZO

Dear

Rev,

I

know this will upset you after all I’ve written for months

and months. But I feel I must tell you the real truth, that

Chipewyan’s granddaughter, Dlune, is a practical nurse at

the hospital where I am paralyzed, entombed in a total-body

cast. And Chipewyan comes to calm me the nights I’m most

lonely, the ones she’s not on duty on my floor and is

working a double on another. Because when she’s off at

night, she sits with me herself.

And

also, that I’m on the ‘surgery-orthopedic’ floor in a

hospital outside

The

crash was a disaster. But I’ve had time to recoup and I

think I’m ready for action that I don’t want you to

interrupt. And she knows what that will be, when I

emerge from my straight-jacket cocoon and into the world of

the living flesh, hers and mine.

The

rest has been fantasy, I admit, as it occurred to me here on

my back since the first envelope, which Dlune mailed to

Inuvik to a Hare friend of Chipewyan’s, who mailed it to you

from there, and so on, to give you the slip. I never left

the country, you see. It was all complete wonderland and

trickery, based on partial fact, and on the possessions

truthfully left me, the books, journals, gear, and so on.

The

sleeping bag I said I walked in last summer represented the

cast in my mind, and I doffed it to pretend I had left my

creaking inertia behind.

“Jack”

and

“mj” are allusions to my own self.

The

police took the photos of the Buick that are enclosed, and

the smile was to hide the pain.

I

crashed at the summit of

And

do you know what else? They’d have been glad to take me with

them, too. My body was sapped of strength when we reached

the pass… and the sky fell.

Who

time-bombed the motor, misjudging her exit?

I

might have saved them…

Now

I remember details. The crash of glass. The bodies in

avalanche lilies, mangled. The car with wheels whistling in

air, steaming and groaning. The smell of gas, then of gas

dripping, everything about to light in flames. The utter

silence which dropped after that like a death sentence,

un-appealed until today.

Because

all noise left my life. Traffic; voices; harangues, jets,

radio; rock and roll; television. In my room I have

forbidden all sound but the soft conversation of Chipewyan

and his granddaughter. And I’ve long since been moved to the

end of the hall, far from patients and nurses, to a bed

where I can look out a window all day at a frozen lake and

peaks in

I

think Chipewyan said they towed the car to

(Later:)

In

truth, Rev – and I only realize it now – I could never have

imagined any of this before. The nightmare I had of the

crash did not come this close to the truth. Only certain

time periods have been accessible. The distant past. The

present here in the room. The uncertain future. But now the

last year is beginning to answer to my searching.

How

can I tie it all together without the essential piece that

is still just a

blurred fragment of a suspicion? I need every bit of

what I can get and more, in order to rise out of this unholy

cast!

The

doctors said my bones were healing slowly since my spirits

were in disrepair. But the X-rays are showing more callus as

of this month.

Come

on, you phosphate salts! Get me out there to that

soul-setting sunshine. Spring is coming. The lakes and

rivers are going to melt, and I want to be there when it

happens, in the flesh and in the spirit.

I’ve

taken

to drinking largish amounts of milk to get the protein and

calcium I’ll need to handle Dlune. I exercise my toes; and

my right wrist, index finger, and thumb are overdeveloped

due to writing. I likewise accept the milk of human

kindness: from her. I can’t talk, can barely move my

lips, and have to communicate with written notes. And my new

friends have given me paper notepads, every single sheet of

which is respectfully stamped: ‘FROM THE BED [not ‘desk’ or

‘office’] OF DR. M. J. LORENZO’. Inimitably cute: right?

But

this part is true: Dlune and I are going to

climb the Peace in a canoe when I’m released from here, if

her granddaddy approves. We’ve talked about it, she aloud,

and I with all the ingenuity and persuasion remaining in my

eyes and right hand…

Here’s

a sample of an evening we spend together. She… enters my

room, dark flesh, dark hair trailing, dark eyes. Fresh from

a day of succor in another part of the hospital. I follow

her liquid progress with my eyes, past the bureau and the

mirror without get-well cards, past the grey steel foot of

the bed beyond a mound of white stiff plaster, which is me,

past the steaming radiator and the (sometimes steaming)

bedpan, with which she sometimes helps me (and more), to

finally stand warmly between me and my view of the tips of

distant mountains, distracting me into the very here and

now, waiting for me to respond.

And

can I reject the first flower to bloom in spring?

Not

me.

Warmly

I ask for the bedpan she just passed.

And

after this strange intimacy we feel even more

electrochemically bound than before, and she announces to

me, ‘Mj’…

I

write: ‘Dlune-tta-naltay….’.

I

confess that’s her complete name. She is

‘Breast-full-of-rats’, or ‘Rat-breast’, or I suppose more

loosely, ‘Rat-woman’. Just ‘Dlune’ in Canadian government

archives. And the spelling is French-Indian, from the book

of Indian tales by Petitot. She doesn’t know how to spell

her full name in

the original, since her people had no alphabet; so she has

to accept this paper compromise.

“Accept

it!

She’s palpitating

after it. She gives me milk through a straw and I accept it.

I,

because of the way her name sounds in English, prefer her

Indian-French name.

I

write, occasionally stroking her eyes with mine: ‘Dlune.

Please sit on the edge of the bed. It won’t hurt me the

least little bit. Please let me hold your hand!’

For

this I have to lay down my pen, and we just look at each

other a while, and hold hands, and our palms become sticky,

and so do a lot of other parts of me, as they must her.

Eventually

I

break this up by writing again: ‘Dlune’, which really

literally means ‘Rats’, but she doesn’t realize it yet. (Why

won’t she communicate with her grandfather on more important

levels?) ‘Dlune, I missed you today. I thought of you all

day, looking at the mountains. A flock of

I

use this primitive Indian imagery with her because it works!

She responds!

’Mj’,

says

she, mending the fractured silence (‘Mj’ is what she calls

me, for I’ve told her that if I’m ever born again from out

of this cast, I want to come back as ‘mj’ and forget there

was ever a Mortimer): ‘I have to ask my grandfather. You

know that’!

I

grab my pen. ‘Well, ask him, then’, I scribble.

‘What are you waiting for? Break-Up? I’ll be out of here in

three or four weeks, they say’.

I

think about the time schedule a moment, attempting to bite

the pen, and decide to leave it all somewhat vague; so I

write:

‘Soon

after

that we must go on our trip up the Peace, and we have to

start getting ready now. I can’t stand the uncertainty of

Chipewyan’s hung up

approval. He might suspect your sewing a tent like

that – day in and day out – if you don’t explain it. Not to

mention: a double sleeping bag. I mean: ask

him’.

I

feel a belated need to soften all this somehow, so I look

into her eyes and write: ‘Please, Dlune, my lovely

Rat-breast’ (I cringe when I see it on paper; but it works,

on special occasions), ‘I’m getting impatient’!

She

looks at me with sympathy. But she is troubled by the

expression, ‘hung up’.

She fears it’s an American expletive.

’ASK

CHIPEWYAN’, I scrawl violently, and she gets the

message.

’Yes,

mj’,

she reacts with consolation, caressing my hair.

Why

do I lose my temper so?

I’m

choked up or something.

The

intricacy of the whole crazy fantasy is starting to get to me, Rev, I

think.

Something

like that.

Mortimer

175. the Lorenzos were

crushed and truly furious, at long last, for the very first

time

Mortimer

lost his first two converts14 with this huge twist in his story,

regretfully. His ‘physical location and condition’ were issues

again immediately. It all sounded terribly real to Rev

and Jo, a hundred times more real than anything he had written

all year. He must have used ‘some literary trick’, maybe a

more convincing writing style than before, they told Sammy

later. For suddenly everything leading up to it seemed

‘fabricated’, leaving the paralysis-and-body-cast talk too

awfully real. It gave them something, at last, very specifically

unthinkable to be worried about unfortunately. And they

did not need that terrible something.

Furthermore:

it was especially frustrating to get this ‘letter’ – for that

was its format, and it looked like a real, sincere letter,

more than any of the other crazy missives – just when he had begun to

sound so much better. Of course, his mood and

mind did seem

better; undeniably, even

within the letter; and the Lorenzos ‘thanked the Lord’

for that. But what about his ‘poor body’, locked inside

a ‘total body cast’? They would have to fly out there to the

hospital! That was all there was to it!

But he

had not named ‘the hospital’; and Rev had already called

“He

was perfectly clear about it,” Jo reminded Rev plaintively and

then with an exasperated sigh, once she had calmed down and

remembered a few of the letter’s quieter and graver details.

And

anyway, finally she realized the ‘letter’ had been written three months in the past,

presumably, because they got the whole darn super-fat envelope

in May, and the ‘fourth attempt’ had taken place way back in

February supposedly. That cute trick really irritated them

both, the three month delay in informing them about all of

this. The more they thought about it, the more they worked

themselves up about it.

“Three months.” said Rev, finally. “Eleven months ago,

more like it. That’s when his confounded ‘Crack-Up’ was,

supposedly.”

They

had been dragged down a primrose path for ELEVEN months. Apparently.

Who knew for sure? How many times had they been toyed with,

and in how many ways? They were flummoxed absolutely for days

after reading the ‘fourth attempt’. And uncharacteristically,

they left the fifth, sixth and seventh ‘attempts’ all unread

for weeks, untouched and sitting there on the kitchen table,

right where they had last dropped them.

They

spent those weeks trying to persuade themselves that physical location and

condition were not the critical issue, because he had

left no choice. But Rev and Jo disliked playing games

with health and whereabouts, and vowed they would tell him

that bit to his face if ever they ever saw him again in

this life. In fact, while at it, they had lots of things to

complain about. And they made a list so that they would not forget one

doggone thing or item. And they got a lot of satisfaction from

that list too. For, as they both thought

suddenly, with more dad-blame outrage than they had gotten in

touch with all year, ‘If he was feeling so darn much better,

then he should be able to stand a few

legitimate complaints from his own parents’.

“Right?”

Rev asked.

“You

may be right,” she admitted.

And this

was the period of time, in fact, when the Lorenzos found

themselves, for at least two weeks, surprisingly close to not

caring to hear one

more crazy word from that darn Mortimer John

Lorenzo ‘in any of

his nefarious forms’, as Rev put it so

artfully. Even though an unsightly wad of unread 8½X11

white sheets of paper still sat in the envelope; and the boy

had promised more after that, unbelievably. But they had lost interest

in remaking mj lorenzo, son or not.

1 This

word-for-word quote of Mortimer’s from Kierkegaard presumably

came from Sickness

Unto Death where The Dane super-psychoanalyzed the

forms, phases and stages of human despair. Kierkegaard, Soren,

The Sickness unto

Death, translated by Walter Lowrie,

2 In

Hindu belief the creator and destroyer of the universe and of

everything in it, including human life itself, is a ‘god’ (in

the pantheon of gods) called Shiva; he is also the god of

sexuality because sex ‘creates life’. Shiva is also the god of

yogic meditation; and one of Shiva’s meditations, according to

Hindu mythology, and especially to the Tantric interpreters of

that mythology, is a focusing-of-conscious-attention upon the

feeling of one’s own and one’s partner’s arousal its very

self. Not surprisingly, therefore, foreplay, love-play,

sexuality and sex in the Hindu universe are all sacred. A nice

description of this belief may be found in John R. Haule’s Pilgrimage of the Heart:

The Path of Romantic Love (Boston: Shambhala, 1992), p.

150ff.

3

November 1960 was when John Kennedy was elected president.

November 1963 was when he was shot dead during a

4 In

Forster’s novel, Maurice,

for example, when Maurice goes to a doctor for psychological

help, the doctor warns Maurice, in a very decided statement,

about the English and their perennial discomfort with the

human body and especially with its naturally-human

animal-mammal sexuality. See E. M. Forster, Maurice (New York:

Norton, 1971), p. 211 (p. 3 of Chapter 41): “

5 See

Appendix B for translation of Spanish language terms.

6 Rev

was remembered for this statement later in a

7 The German word dorf means village; and the German word kirche means church.

Mortimer is returning here to the theme Jack introduced in