go ahead to subsection: [145]; [146]; [147]; [148]; [149]; [150]; [151]; [152]; [153]; [154]; [155]; [156]; [157]; [158]

145. Mortimer was

deemed ‘the problem’

The

third section of Mortimer’s overwrought and overweight tome

of winter writing encouraged Jo Lorenzo less than the

second section to believe her son had progressed toward

making a new and lovelier person of himself.

But

she was wrong. She did not understand the ‘third attempt’

because of its offhand brainy style and she thought

Mortimer’s lying in bed the whole month of January ‘to

think’ was a bad sign. Whereas in reality he was using the

month to get to the bottom of things once and for all and

was discovering that he was not to blame for mj lorenzo’s problem

after all. This was important stuff for the future of

humanity, said pundits, if the human race was to avoid

annihilating itself and have any future at all.

On

the other hand, meanwhile, Jo Lorenzo was starting to get

the idea that Mortimer was indeed mj’s problem, not ‘Jack’.

Because Mortimer would never be much use to the world or mj

‘without someone around to liven him up’, she told Rev when

they read the chapter the first time. Mortimer could never

do much that was useful or interesting without Jack. Or

without somebody with

life, she clarified. ‘Stuffy old Mortimer’ would not

have made it to

the island without Jack, for example, she

claimed, if Jack had not by the Lord’s love and grace been a

geography nut. Even Mortimer’s ‘inspired’ idea, the ‘rule’,

as he called it, that he was to ‘spend the winter’ – ‘like

the geographic explorer Mackenzie’ – ‘on an island in Lake

Athabasca with an

Indian woman preparing for a spring trip up the Peace

River’: had all of it been dreamt up by Jack

and passed on to Mortimer BY JACK all the way

back at the Arctic! She was a little heated about this.

And

Jo had also figured out by now, as she told Sammy Martinez

years later, that mj’s first experience of freedom in his

life, his western and Arctic spree, had ‘burnt Jack out’

quickly. It was part of the reason she sometimes felt like

favoring the ‘Jack’ side of her son. Mortimer had sneakily

‘gotten rid of Jack’ one more sad time by simply letting him

have his heyday and burn himself out, she said. And now

‘dull old Mortimer’, as she called him, stumbling along

lifelessly, was dismally drained of spunk. Jack was the only

part of mj that had any ‘spirit’, she thought. And that was

why the third section of ‘Part II’ of mj’s ‘first stab at a

modernistic novel’, as she called The Remaking for the rest

of her life, also

came off as just one

more half-hearted ‘attempt’ to get his two

sides working together. Because poor old half-dead Mortimer

always wearied of life in no time without Jack around to

‘inspire’ him and keep him stimulated in various ways.

146. but where WAS Jack? what

had happened to him?

Adding

to Jo’s belief that Mortimer was ‘half-hearted’, and to the

pundits’ same belief eventually (many of whom said Mortimer

had no humanity or heart at all), was the

fact that by this point Mortimer had stopped writing to his

parents about that infamous part of mj that was supposedly

locked up on a psych ward. Mortimer rarely mentioned ‘Jack’,

as if he thought he could get rid of him in such a way. And

when he did refer

to Jack’s physical whereabouts he mentioned him not as a

patient in a psych unit, but as a specter-like figure lost

in a foggy white-out, stumbling around a vast, empty,

snow-blown flatland, an imagined dagger in hand, as it were.

Mortimer wrote his parents in the ‘third attempt’, in fact,

that Chipewyan had helped him set up trap lines in a pattern

radiating out from their cabin across the lake ice and down

the Slave toward Fort Smith. And whenever he went out to

check the lines he

feared he would run into Jack and be killed.

In

time, because of hints like these, a remarkable thing became

apparent to some of the earliest pundits, though Mortimer

had never spelled it out in the pages sent to Rev and Jo. To

many it seemed that Jack

must have escaped from the psych unit.

147. Mortimer glorified Reason

But

whatever had happened to Jack, nothing was about to stop

Mortimer from writing or from using his head to solve the

world’s problems. He was not about to leave it to unthinking

Jack-types to determine the world’s future all by

‘them-thoughtless-selves’. His ardent brainstorming of

EVERYTHING was a given

in the same way that endless brainy theologizing about Jesus

Christ AND EVERYTHING ELSE had been a given for churchmen

like Paul, Origen, Augustine, Abelard, Aquinas, John Calvin

and so on. Such serious addiction to mentation had

been a given since the day centuries back when Western

civilization had decided that dwelling in airy realms of

mind and spirit, pretending to be ‘God-as-Logos’ (as some

theologians called this power to thrive in pure and airy

thought-realms), was

the most valuable, beautiful and important thing under the

sun, the ‘highest’ profession in the land.

148. Mortimer used

Reason to analyze savior complexes and impotencies

The

‘third attempt’ glorified reason, therefore, the pundits

made clear. But it studied two other traits of Mortimer’s

too, his ‘savior complex’ and his ‘impotence’. And those two

sub-sections, both of them at the end of the ‘third

attempt’, sailed straight over Jo’s heart when she finally

got to them, all worn out, by then, from Mortimer’s profound

thinking. It was more than enough to keep up with his many

various analyses of great sages. She saw no need to think of

her son as any kind of ‘savior’ when he could hardly get out

of bed. And she was not going to listen to the slightest

reference to sexual impotence in any man she knew, least of

all in her son. When the topic came up at the end of the

section, therefore, all of the Puritan Pilgrims of Plymouth

Rock rushed forward to rescue her; and Queen Victoria

hovered above them floating in the air, sponsoring them in a

frumpy dark skirt that seemed to have stayed in place

Victoria’s whole life. And just that fast Jo jumped to the

assumption that the ‘impotence’ Mortimer referred to was his

own powerlessness in

general.

149. how Mortimer

used the universally hated ‘lists’ to answer his number

one question

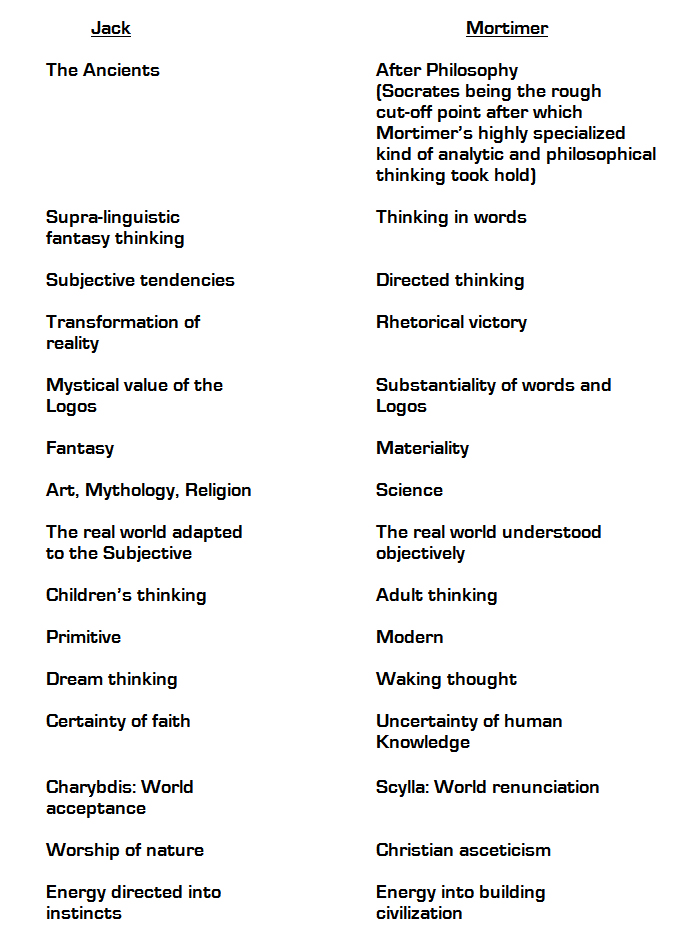

So

the early pundits had to clarify that, while Mortimer may

have been ‘half-hearted’, as Jo said, when it came to

dealing with Jack face-to-face; he was anything but

half-hearted when it came to dealing with Jack on the written page.

From page one of the ‘third attempt’ Mortimer showed an

impressive quantity of reasoning capacity despite any

‘half-heartedness’ shown without Jack around physically to

keep him company. Just six months after the Crack-Up his

ability to use his head for cogitating looked substantial

again, more than enough to do the job. And so, using his

reasoning faculties as he had for years he examined again

and again those soon-to-be infamous and hated ‘lists’ of

polar-opposite character traits, lists he had constructed by

studying scholarly books written by Kierkegaard, Jung,

Sartre and McLuhan.1

Sitting in the cabin Chipewyan had built and on the bed the

old man had made by hand, he stared for hours at a time at

his sketched list-summaries of those four authors’ thinking.

Maybe it was true

that he had done so already a hundred times. But one

more time he had to try to finally get to the very, very

bottom of the central matter of his existence, seemingly:

THE ISSUE OF

OPPOSITES.

150. but what WAS the

number one question? it was: ‘what is Western

civilization’s number one problem?’

This time – as he wrote Rev – he was going to finally

solve the problem by asking the right question,

hopefully. Which he now thought might be this question: why did so many of

the greatest thinkers of 19th and 20th

century Western civilization preoccupy themselves with

splits, shifts and imbalances in human character?

Each had his own take on the problem, of course. But all

shared the same concern that within the Western world the

polar opposites of human nature might not be distributed or

blended properly within individuals or within society at

large. They worried about the possibility of extremely exaggerated

one-sidedness in individuals; and in society; and

about the likely destructive results.

And

at the same time wherever the two opposite sides were seen

as being nearly equal

in power, each despising and fearing the other and/or acting

unwilling to compromise and share power, all these sages

worried about the possible destructive consequences for

individuals, and for society, resulting from such ‘hyperpolarization’.

So: that was it. That was the name Mortimer gave to this

problem which all of his favorite sages seemed to be

describing, ‘hyper-polarization’.

151. Mortimer defines

the number one problem as ‘hyperpolarization’

For

years Mortimer had relished studying the brilliant minds of

history and suddenly it hit him that in the past hundred

years, at least four of his favorite thinkers had all

sounded the same alarm: that his very own Western civilization

had been handing its members a set of cultural values

that steered their character development along a path of

hyperpolarized choices, starting at birth, in a way that

made it hard for them later in life, if not impossible,

TO MAINTAIN HEALTHY EMOTIONAL BALANCE.

152. Mortimer

analyzes hyperpolarization as described in scholarly works

by Sartre, McLuhan and Kierkegaard

Sartre

in his thick book, Saint Genet (1952), for example,2

which amounted to an exhaustive quasi-psychoanalytic study

of Sartre’s contemporary, the French novelist and

playwright, Jean Genet, maintained that Genet had been

tormented throughout his life by an urge to act outwardly like a

jokester criminal while he continued to feel inwardly like a

tragic Catholic martyr. This split in identity was so extreme and difficult

to heal, said Sartre, it would have buried any Frenchman but

an artistic genius like Genet. And for the suffering which

it kept causing Genet, Sartre blamed the aberrant,

flesh-disparaging, dehumanized crackpot Western-world way of

living life in the world, as Genet had experienced it

growing up in conservative, old-fashioned Catholic Christian

France.

Later,

in 1964, a Canadian English professor, Marshall McLuhan, in

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, wrote

about this ‘split’

in the character of Western civilization in a different way,

claiming that this civilization was dysfunctionally split

and hyperpolarized because, on the one hand, it lived its

day-to-day life in an up-to-date way as part of a

planet-wide tribe of Jack-types who vibrated

spirit-connectedly as one electric body

(constantly connected to each other by a nervous system of

telephone, TV, radio, etc.); while on the other hand this

Western civilization continued using its mind as it

had for centuries, the way a dry, out-dated, machine-minded

Englishman such as Isaac Newton (or Mortimer) might have

used his thinking machine.

And

meanwhile, as far back as the mid-nineteenth century,

Kierkegaard, in Either/Or and other works,3

had criticized a too carefully structured Scandinavian

society which had become split and hyperpolarized because it

had, on the one hand, overdeveloped in its citizens an

excellent talent for establishing rules and living by them,

just like Mortimer; while it had, on the other hand, left

its citizens with an under-appreciation for Jackian realms

of human living, for beauty and spirit, including art, the

body, and ‘true’

religious feeling.

153. Mortimer’s

favorite sage of all, however, remained forever Carl Jung

Most

important of all, however, was Jung, insisted Mortimer. Carl

Gustav Jung had maintained throughout all of his long life,

through all his innumerable scholarly works, with incredibly

detailed supportive documentation amazingly unearthed from

just about every field of knowledge known to man, that Western civilization

was dangerously off-kilter and therefore had become hyperpolarized in a

variety of ways. In Psychological Types (1923), he

had pointed out that Western civilization had been given a

kick-off by church fathers who literally cut off their

testicles to feel holy, because they could

not figure out how to enjoy sex and God at the same

moment; and who sacrificed a love of rational

philosophy in a desperate search for heart, because they could

not figure out how to think and have heart, both, at the

same time. And now, twenty or so centuries

later, the ‘Western’ civilization that those unbalanced

souls had set in motion long ago, was still so sickly

and imbalanced and over-polarized, therefore, THANKS

TO THOSE VERY SAME IMBALANCED EARLY CHURCH FATHERS and their

look-alike philosophical offspring down through the

centuries, it was at risk for chemically obliterating itself

into nothingness, if not the whole rest of the world as

well. Because its individual members and component societies

still

overdeveloped some parts of their human nature and of their

psyche (parts of the mind, personality and emotions) in a

way which de-humanized them, while they left other parts of

their human nature and psyche that were equally important

underdeveloped, thus de-humanizing themselves even further.

Jung’s treatment program had been carefully designed for fixing and balancing

the whole of Western

civilization, therefore, as much as for fixing and

balancing out-of-balance individuals.

154. Jung said

hyperpolarization was Western civilization’s fault not

Mortimer’s

Suddenly

it seemed obvious to Mortimer that if his whole civilization

suffered the same malady he did, then he did not have to

blame himself for mj’s disintegration. He felt a little less

guilty about mj lorenzo's ‘hyperpolarization’ and past.

But

what about the future? How much more harm might a

Frankenstein’s monster of such enormity as ‘the Western

world’ cause? And anyway, bucking against the momentum of

such a Leviathan as one’s whole civilization, and such a

powerful civilization, too, in the world of Mortimer’s day,

what could one little Mortimer accomplish? Or even,

forgetting civilization for the moment, what hope remained

that mj lorenzo might ever balance his own little individual

hyperpolarized self?

Mortimer

asked himself these questions rhetorically only,

of course; for by this trick he could resemble a great sage

like Jung, who could ask the most weighty questions

imaginable; while at the same time Mortimer did not have to

work hard in the real physical world like the real

psychiatrist, Dr. Carl Jung, M.D., solving difficult

problems explicitly, since Mortimer remained in bed,

avoiding the real physical world and its people and

psychiatric patients.

But,

always lying on his bed, of course, he never gave in to

hopelessness completely, and for that he deserved a little

credit at least, said his defenders. He did manage to answer

his own big questions implicitly,

in his own way, by never ceasing to use his power of reason, and by

never failing to write

down the results of his thinking. His continued thinking implied,

in other words, that he thought the answers would be found some day

through his continued thinking!

Apparently

it was hard to shake loose from Mortimer a certain deep-seated

conviction which was part of his make-up as mj lorenzo,

namely: the conviction that he had been born into the

world to save it with his reason and his writing about

that reason, notwithstanding any failings he might

suffer, including severe depression, pitiful one-sidedness

and grave life-depletion.

155. Jung’s Symbols

of Transformation receives Mortimer’s first prize

because it gets Mortimer off the hook

All

of these discoveries had improved Mortimer’s understanding

of poor ol mj lorenzo and of mj’s sorry split into two very

different ‘halves’ that warred with each other constantly. And that was ‘great’,

Mortimer wrote his parents. But: Carl Jung, he said,

in his Symbols of Transformation, had pegged Jack and him

better than any portrayal he had ever come across. The

‘list’ in the envelope at this point, the list of

polar-opposite traits he had taken hours and hours to ferret

out and jot down, drawn from that tome of Jung’s, might look short to

some people, but the list made up in accuracy and

completeness for anything it ever may have lacked in length,

he said. Because Jung’s handy conceptual dichotomies cut

right to the heart of the matter and did so succinctly,

elucidating the very

most telling distinctions between mj’s two sides,

Mortimer and Jack. Jung captured the essence of the battle

between Jack and Mortimer better and more completely than

McLuhan, Kierkegaard, Sartre or anyone he knew. Maybe

because instead of using everyday language as those scholars

did, then combining it with their own new philosophical

language, Jung restricted himself to the original conceptual

language of Western civilization’s humanities and sciences,

i.e., the language of Greek myth, of Western philosophy and

Christian theology and, eventually, of science, meaning

especially of modern anthropology and psychology. And all of

these more complex terminologies represented and reflected the very conceptual

constructs which had come to (1) define ‘higher’

Western thought and (2) ‘screw up the

Western world’s mental health’, as Mortimer put

it, far more than any kind of everyday ordinary language or

modern philosophical movement would have done. This

explained Jung’s triumph over the others, thought Mortimer.

The

early pundits raved in agreement with this observation about

‘plain language’. And those who joined their growing numbers

in the eighties and nineties raved likewise. All forever

said a loud amen; and eventually they added that had Western

civilization simply stayed with ordinary human language

and ordinary human thought, then its whole civilization,

‘right from the get-go’, would never have dehumanized

Christ’s teaching and thereby dehumanized the Western

world’s people and history. If Western civilization had not

so quickly tried to unburden itself of its own human animal

nature, if it had not so soon succeeded in stripping itself

of its own real flesh and blood, it might never have had to

end up in such distress and imbalance as it suffered

presently, intra-psychically, politically and even

electromagnetically.

C. G. Jung: Symbols of

Transformation: An Analysis of the Prelude to a Case

of Schizophrenia. (1956).4