go ahead to: [subsection 140]; [141]; [142]; [143]; [144]

140. the early

Remaking pundits survive the ‘

In

the early 70s a few Remaking psych pundits – or psycho

maybe – survived a whole warm spring weekend holed up in a

funky bay-windowed Victorian apartment in Powelton Village

smoking Lebanese hash, popping white crosses and workshopping

Parts I and II of The Remaking trying to organize a

calendar of sequenced ‘second encounter’ events.

When

the ordeal was over and they were found alive, amazingly,

they celebrated by composing a letter announcing and

outlining their triumph ‘joint-ly’, then mailed the darn thing to High Times1

and never saw it published (sadly but fortunately

for the future of mj and Remaking punditry). And so, after

a year of reading High

Times cover to cover looking for the thing and never

finding it they gave up and typed up their outline more

carefully this time and handed it out to pundits at

workshops free. And it spread worldwide and became a

standard reference for Remaking punditry.

The

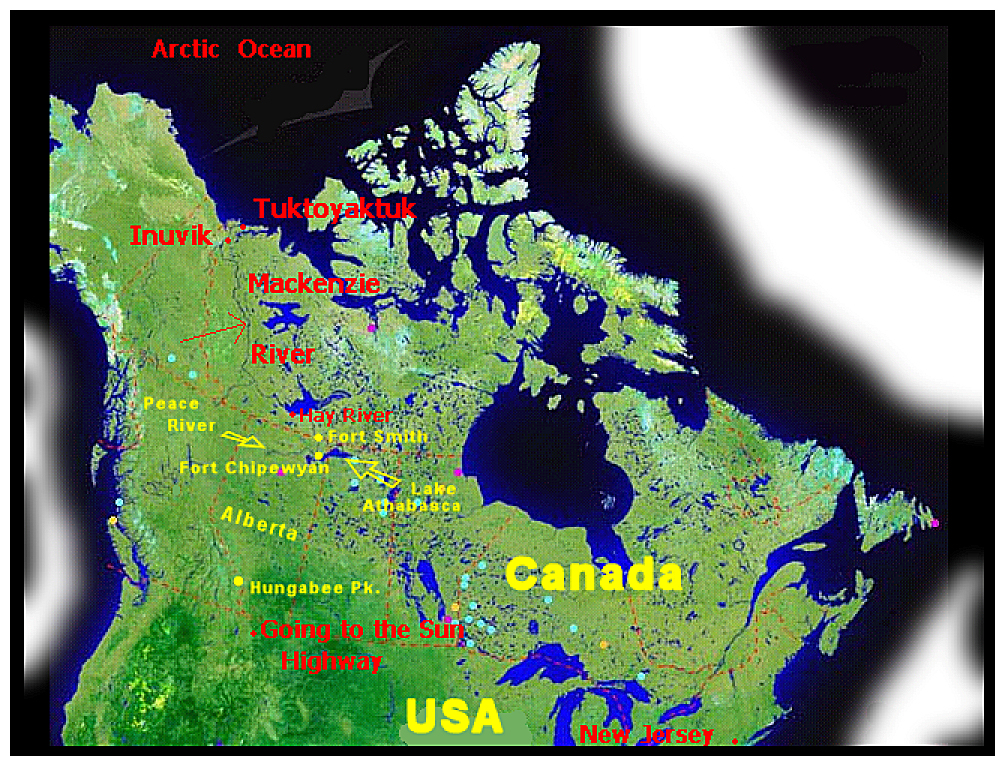

Fort Smith Chronology Outline’s reasoning went as follows.

If Freeze-Up had hit mj lorenzo in early November and if

Mortimer had stayed in

141. the old man

and the island

The

rest was easier to sort out: Dr. Mortimer, a few days

before 'derelicting duty' and disappearing, had mentioned

to a nurse longingly how much he wished he could ‘spend

the winter on an island in

She

ran over from classes the next day and knocked on the

doctor’s door. They talked in his makeshift office in the

storage closet and before she left she suggested that he

might find her grandfather who lived ‘on an island in Lake

Athabasca’ very close to Fort Chipewyan and who probably

could help him find a place to stay for the winter.

Mortimer

found both island and grandfather because few others in

modern electrified

Luckily for posterity, as early Remaking pundits

sighed. For mj had been dangerously near disaster; but

good things came from this big break. And the old man who

bore the name of his tribe would be THE beginning, finally, of

‘Mortimer’s re-humanification program’, they said.

Other

pundits disagreed, however. They claimed that Dlune, more

correctly, was the beginning of mj lorenzo’s ‘becoming

human’ finally; because she had sent Mortimer

to the man. She had gone out of her way

to do so with just that in mind. And everyone agreed in

the end that it was Dlune who had saved mj’s life, more

than the old man. But it was impossible to measure such a

thing with certainty, of course.

The

old man would prove to be ‘very important’ to mj’s

survival and remaking in any case. And Mortimer’s ‘second

attempt at a meeting’ began with two allusions to the man,

allusions that were vague

and indirect, as often had been mj lorenzo’s manner

of saying the very most important things, whether writing

as Jack or Mortimer.

And

after these two very indirect allusions to the old man

Mortimer suddenly became uncommonly plain about his

circumstances, as if an important nerve had popped back

into life inside him finally. Pundits liked to say that

Mortimer had acquiesced for a minute, finally, and

surprisingly, to descending from that highfalutin Logos

language locus where he had lived until then, from that

windy, craggy high place where vague and abstruse

intellectual references to books and concepts kept

‘circling and wheeling and banking like flocks and flocks

of Arctic terns’, ‘periodically alighting in complex but

analyzable patterns’. Finally, they said, Mortimer was

going to ‘talk plain’ about the kinds of things the rest

of the world talked plainly about every day, like the

weird old geezer living in the house; or the young

foreigner visiting the neighborhood. Mortimer was going to

let everybody relax and feel at home for once, so they

could work less hard at understanding his freaky

communication. He seemed ‘almost kind-of normal and

human for a page or two’, actually, said the

pundits, though stiffness in his writing style showed

through (especially compared with Dr. Lorenzo’s ‘Jewish

street-cholo’ of later years). And other humanifying

changes would follow, they said, one by one as

winter progressed ever so slowly.

But

this moment of light, they said, was the very,

very first glimmer of light, the first

flower to pop up through the snow of Mortimer’s deeply

frozen humanity.

142. I’m living

with an old Indian in northern

from

If

what McLuhan says about the ‘Global Village’ is true,

Rev, that all earthly humans now live in ‘one great

electrically connected village’ covering the entire

globe,2 then that

‘village’, like any normal tribal village, must have a

tribal medicine man ambling somewhere around the

village, as it seems to me.

And

the doctor is hope, as they say.

And

hope is magic.

And

Jung writes at length on the archetype of the

‘magician’, the one who magically heals.

And as far as I can

tell, though he never claimed the title, he, Jung himself,

has got to be the ‘global tribal magician’ I refer to,

the global-village medicine man.3

…………………………………………………………..

The

following lines, Rev, are from a section of Mackenzie’s

Journals called ‘A General History of the Fur Trade from

It is not necessary for me to examine the cause,

but experience proves that it requires much less time for

a civilized people to deviate into the manners and customs

of savage life, than for savages to rise into a state of

civilization.4

The

European

trappers in

This indifference about amassing property, and

the pleasure of living free from all restraints soon

brought on a licentiousness of manners which could not

long escape the vigilant observation of the missionaries,

who had much reason to complain of their being a disgrace

to the Christian religion…. They therefore, exerted their

influence to procure the suppression of these people, and

accordingly, no one was allowed to go up the country to

traffic with the Indians, without a license from the

government.5

Good

grief!

What a solution.

Who

needs a license to meet with his own soul, Rev?

……………………………………………………………..

The

truth

is, Rev, I’ve been lucky enough to run across an ancient

wrinkled ‘Indian’, a doctor like me, a medicine man

named Chipewyan, and he has been teaching me to hunt and

trap and catch fish Indian-style through the ice, and

give up my crazy diet of berries, wisely, since there

are no berries now. He has let me live with him

rent-free on the understanding that once I am broken in

I’ll help him

this winter to

stay alive – by chopping and hauling wood mainly

and keeping the fire going. He is undernourished,

tottering at death’s doorstep, probably. But who am I to

think less of him for it? I’m in worse shape and have no

patients either. Nobody comes to either of us for help

these days. But they are the fools. Because his limbs

may rattle, and his voice, but his mind – his balanced,

calm mind –

has been sharpened

like an

arrowhead.

And

with that sharpness he tells me his tribal legends,

helping me get through the dark depressing midwinter

days, an endless affair. But I screw up and fall asleep

while he is rattling on and on and I dream ancient

northerly dreams. I can’t tell one day from the next,

daytime is so dark. I try to remember the tales so I can

write them down later, but I get confused about what I

have heard and what I have invented or dreamt, and it

makes me mad. So I try to stay awake and keep him happy

and me too, because he is in some kind of

timeless tribal heaven when he is telling these

stories, Rev, and that affects me.

Yet

I fall asleep again invariably. I’m restless when I

sleep and I shout and cry from the bed and wake the poor

guy up wherever he has gone, usually to the other room

by this time to sleep on the floor where he sleeps

always. He hobbles up and I see his parchment face and

flat eyes in the darkness barely, waiting for an

explanation from me, probably. He is patient, Rev, if

you ask me. He is superhumanly patient. He never

complains like I always used to whenever dredged up at

the hospital to go and do ghostly intern acts in the

night.

“Because

you’re

sick,” he says. That’s what he thinks. So I need to be

‘visited’, he says. And I am ‘dumb’ too, he thinks. But

I’d have to

be in his

world. Yet in mine

too? He doesn’t say so, but yes, he knows I

am dumb in my world too, anybody’s world. And he figures

I’ll sleep better and bother him less if I’ve seen his

face, old and beaten as a big northern tree, as the bark

on the wood of the dock-post tree, the one that was here

half a millennium already when Mackenzie climbed out of

a canoe to put in the winter of 1789 in this spot and

tied up his boat to that tree. He guesses I’ll be more

content and won’t startle in my sleep again, and he

might get to sleep the rest of the night for once, poor

guy, if he just gets up and comes to ‘visit’ me whenever

I freak out like that in my sleep.

What

is happening to me, Rev?

143. the first part

of the story Chipewyan told

I’ve

written down the first half of the story Chipewyan told

me – a few hours ago, I think. It’s his best yet. And

that made me stay awake and write it down.

There’s

still a lot I don’t understand about his world probably,

like how they tell stories and what things mean. I

thought at first when they got whisked to the higher

place that Chipewyan called ‘heaven’ or ‘sky earth’ or

‘foot of heaven’ they died. But then they came back;

always; and Indians have never been into resurrection to

my knowledge. So finally I got the idea that the high

place must be the one where you go for visions or a new

perspective, to learn a lesson, get insight or have a

breakthrough in understanding everything about your

universe.; that kind of thing; like an ‘Indian’ or

‘Native American’ ‘vision quest’ when braves used to go

into high mountains and expose themselves to nature in

the extreme to weaken their mind and body so as to dream

dreams that gave them and their tribe wisdom and power.

Then

there’s

another pattern that runs through the tales. Often there

are two heroes who are polar opposites, most often older

and younger brothers; and such a trick works to suggest

two sides of a person or tribe. So the Chipewyans, or

‘Dene’ actually, as they call themselves in their own

language, probably are not so unlike us in basic ways.

They just have their own unique ways of talking about

it, that’s all.

I

make an exercise of hanging out in Chipewyan’s world of

legend in my head. So I don’t go out. Just to the post.

That’s all. And I buy things that relate to that world

of the tales. I try to buy items which represent or

remind me of the phantasmagoric world opening up like a

fantastic flower popping through the snow.

The

stamps

on the envelope I’ll mail you eventually will be of

Indians. The paper you are holding right now is made

from pulp at

I

may be coming around, though, to spending more time on

the floor too, because I feel too high up in the air on

this bier-y bed of a litter, especially around an old

guy who enchants with stories always telling them

sitting the whole time on the cold, humble floor.

“Oh,

old Indian, get me back to the earth again, please.

Can’t you, some time soon?”

Chipewyan’s

people

usually learned a tale by hearing it over and over then

telling it time and again until they got it down. They

had no alphabet or writing, of course, so had to pass

down knowledge by storytelling. It’s easy to picture the

scene. The men of the tribe gathered around a campfire,

old ones clouting young when they made a mistake

relating a tale. This was why stories suffered little

alteration over centuries sometimes.

Unless,

of

course, a group wandered off to new territory and

remembered everything wrongly because they had no one

with them who could remember it right, like the Navajo

and Western Apache when they wandered off from the

far-northern tribes and went south. The ancestors of all

three groups are thought to have spoken one language at

one time, called ‘Athabascan’, and to have lived near or

with each other. And since the native race of North

America is thought to have gotten here by crossing the

Bering Strait, then it must be that the Navajo and

Western Apache are descendants of a group that broke

away from a tribe here in the north and went farther

south looking for a better life.

Today

we ate Chipewyan’s meal of elk venison and a trout’s eye

and we puffed on an old medicine pipe which may have

affected me. And then while the stone-dead silence of a

hell-black universe surrounded us and our island hut,

and the rich, sweet-smelling fire crackled and shot

sparks, Chipewyan, in his droning, cracking voice told

me this tale.

Did

it all really happen, Rev? Or am I just dreaming?

TTATHE

DENE

The Appearance of Man6

ELTCHELEKWIE

ONNIE

The

Story of Two Brothers

Origin

of the Beavers, a Chipewyan Sub-tribe

In the beginning there

was an old man who had two sons. One day he said to them:

“My children, climb into your canoe and go hunting, for

there is nothing here to eat.”

The two sons were

obedient and set out immediately to hunt. The old man said

to them: “You shall set out toward the West, for there is

where you shall find your original land of birth, and

there alone is where you shall be happy.”

Thus they departed.

By the fourth day of

their journey they arrived at a waterfall named Eltsin

nathelin, or The Whirlpool. There they caught some game

birds: but by the time evening had come, they knew not

where they were and had quite lost their way. The

following day and the days thereafter, the two brothers

made little headway. However, they had eaten their little

birds, and advanced along deserted and steep river banks

to the

“My brother, my older

brother,” said the younger of the two to his brother,

“this country does not resemble at all our own. Where do

you suppose we are?”

“Alas, my younger

brother,” returned the older, “I do not know any more than

you; but don’t worry, just keep going.”

All of a sudden the

two brothers heard voices from underground, the voices of

gigantic people (Otchore), who lived along the northern

shore of the lake. In front of the mountain a little giant

and sister were playing together. This conical mountain

was their teepee.

“Oh, what small

people,” they cried with joy, when they noticed the two

Dene brothers. They ran to them, took them in their hands

and placed them inside their mittens, and one carried them

in this way to their parents.

“Look, mother, father,

what little bits of people we have found along the shore,”

they said cheerfully.

“Don’t you make fun of

them,” said the gigantic father, who was a strong brave

man. “My children,” he added, addressing himself to the

two brothers, “stay with us, for no one will do you harm.”

This saying, he served

each of them a trout’s eye, from a giant trout.

The two Dene thus

stayed and lived at the Dene-cheth-yare, on the north bank

of the

But in the end they

grew weary of this life of ease and asked if they could go

on their way.

“Of course,” said the

giant.

He made them pemmican

of fish and gave them each two arrows.

“With this male arrow,

you may kill the male elk,” he said to them, “and with the

female arrow you may pursue the female. The two arrows are

both very powerful. They return of their own accord after

they are shot: therefore don’t go running to fetch them,

or evil will befall you. I swear this to you absolutely.”

The two brothers

promised to do everything as told and left.

Upon their departure,

the good giant indicated the setting sun as the point upon

the horizon where they should find their country of birth

and counseled them to head in this direction.

Shortly after their

departure from the home of the good giant, the younger of

the two brothers espied a squirrel perched on a large fir

tree and let fly one of his arrows. Then immediately he

ran to fetch it.

“Oh, my young brother,

be careful; do not even touch it,” cried the elder

brother. You know that they have sworn to us not to. It is

quite bad, one should think, to disobey.”

But the younger

brother was obstinate.

“It is within reach,”

he cried to his brother, “I can get it.”

He then put out his

hand to grasp it, but it shot upwards in pursuit of the

squirrel, who was making fun of the hunters.

“Ah, see if I don’t

get it!” he exclaimed triumphantly.

But it escaped and

shot away again, and always again. Finally the young

brother seized the arrow. But it shot away like lightning

and aimed straight for the sky, dragging behind it the

poor unfortunate younger brother. The arrow introduced him

into heaven.

Above us there is a

higher country in all appearances like that which we

inhabit. When the young man arrived there, he found it

frozen over, and on top of the snow he saw a great number

of footprints of animals whose flesh is edible.

He saw there also a

great white road, bordered by trees in fruit and by

roadside markers. By the road were a pair of freshly made

snowshoes planted in the snow and apparently waiting for

him.

The young brother,

carried far away from his homeland by his disobedience,

slipped on the snowshoes and followed the white track. He

thus arrived at an immense tent inside of which he

discovered three women who gave him hospitality.

The eldest, the mother

of the other two, said to him secretly:

“My son-in-law, I warn

you that my daughters are evil. They are unfaithful to

men. Therefore do not trust them. Do not ever sleep with

them, and do not even look at them sleeping.”

Having said this and

in order to prevent an alliance between the young man,

whom she found handsome, and her daughters, the woman

blackened his face entirely with char, hoping that he

would not be liked by them.

In the evening the two

heavenly daughters returned from the chase, for they were

like Amazon huntresses. The one was named,

“Breast-full-of-weasels” (Delkrayle-tta-naltay); the

younger, “Breast-full-of-mice” (Dlune-tta-naltay).

When they caught sight

of the little black man who was seated in their mother’s

tent, they could not keep from laughing out loud, and

mocking him.

The old woman was

triumphant. But the following day, the young man, stung to

the quick, washed his face and hands and appeared so

attractive to the two sisters that they both cried

together:

“I want him! I want

him! He will be mine.”

In vain the old woman

made opposition to their union, for the two daughters

threw themselves upon the handsome young man, leading him

away to their bed and making him sleep between them.

But they had no sooner

passed one night together, despite the mother’s

interdiction, than there opened up beneath the young man

an abyss, and he was swallowed up alive into the breast of

the sky-earth.

“Nari!” (“Poor

fellow!”) cried the woman, when she saw that he had

disappeared.

“There goes another

beautiful young man whom you have ravished away for me,

you evil enchantresses, you!”

Jo

Lorenzo flipped through some pages that came after

Chipewyan’s tale. “What happened to Jack?” she asked, for

the next page said ‘third attempt’.

“He’s

still in

“It

wasn’t much of an ‘attempt’

at a meeting,” she said. “It was a short letter for once,

anyway.”

“But

what was it about?”

“He

seems different,” she offered.

“But

why the Indian thing? Is there a message?”

“He

seems a little bit better maybe. Don’t you think, John?”

“Is

that the message?”

“It

could be.”

“But

why ‘favorite story’? Game birds and giant teepees? When I

tell a story from the pulpit there is a reason that has to

do with the message and I make the reason clear to the

congregation. I don’t get it.”

Jo

didn’t either. “He says he’s ‘in an Indian world’.”

“So?”

“Maybe

he’s getting better, John.”

“By

copying Indian tales out of a book by a Frenchman?

Mortimer doesn’t write like that. Neither does Jack. They

are not his words.”

“Let’s

read more and see. He’s trying to fix himself,

isn’t he?”

“Yes,"

Rev allowed. Now that he has found himself,

meaning now that he

has found ‘Jack’, that is. I think he needs to be fixed.

Yes,” said Rev, clearly associating his son with an

un-neutered dog.

But

Jo heard a gentler meaning or pretended to. “Is he a

little better, then?”

“"Well,

I don't kno-ow,"

said Rev as if he had heard someone else say that and

mimicked him. “Beats me,” he said in the same way. The

shoulder twist was familiar too.

“Then

we have to keep reading until we do know he is

better, John. Don’t we? He sent us five more ‘attempts’

here.”

“Attempts

to drive yoo-coo-koo-too,” he said with the mouth of a big

cuckoo.

“Attempts

at fixing

himself,” she said carefully and softly, as if as soft on

Mortimer as on Jack. And as on Rev.

“I’ll

vote for that. You read, then,” he directed less

acrimoniously. And as she separated out the papers of the

next section he said again, in the same annoying drone, “I

just don’t get the whole Indian thing.”

“It’s

two brothers on a trip, isn’t it? One obeys his elders.

The other does not and he suffers. But

others can learn from his mistake and suffering and that’s

why the tribe tells the story, John. Just like you used to

read the stories of Horatio Alger and David Copperfield

and today we’re not poor any more.”

“Groucho

Marx went to synagogue smoking a cigar. Does that make me

a pillar of fire?”

“‘Don’t

make fun of

them, John’,” she stared at her husband, “as the giant

father said to the giant children about the two tiny

brothers.”

So

they stretched their sacred Puritan tradition of reading

excellent moral fare at the kitchen table after dinner to

an unprecedented extreme and plowed straight into the

‘third attempt’ of The

Remaking, though it was after midnight already.