272. Dlune’s trek to

find her dreamer and get him down from the mountain

It is at such an

hour in the late evening two whole days later, after two

very long, clear, brilliantly sunlit days of watching from

Wiwaxy, that Dlune still waits there, hoping to catch sight

of mj emerging from the forest along the distant edge of the

lake a thousand feet below. The shadow of Wiwaxy is about to

overtake the other shore and mj is still nowhere in

sight.

‘I’ll be back by

dark’, he had said: or ‘two or three days’, when they had

talked about it other times; but ‘one day’ when he stood

right here on this spot and promised her.

Dlune begins her

descent from Wiwaxy, down toward camp, alone in the dusky

shadows, stumbling, cutting her feet, falling once, then

slipping and nearly sliding off the ledge to drop straight

down a thousand feet into the freezing-cold glacial lake.

She spends the

shortest, most sunlight-affected night of the year alone and

frightened in the tent near the lake.

Even before dawn

(which at summer solstice is the earliest dawn of the year

in any case, and is especially early when you are so far

north), she rises without benefit of sleep, kicks frost off

the sleeping bag, pulls on khaki pants, hiking boots and a

bomber jacket and collects the black hair on her head into a

straight unit which she ties with a white bow. Her face, a

deeper dark brown than in winter because sunned, and pulled

taut at the mouth corners a bit, pushed and rumpled in the

middle-forehead, naturally tinted rose on the high-placed

cheek bones and glowing even in the tent’s relative

darkness, her face – her face reads: serious. Intent;

worried. A little.

The frown

intensifies as she laces the top holes of her left boot and

pulls the string into a tight bow.

She straightens

the tent, packs some food and water in a knapsack which she

flings across her shoulders, and departs along the meadow

path, bound for the near side of the lake, munching dry

bread.

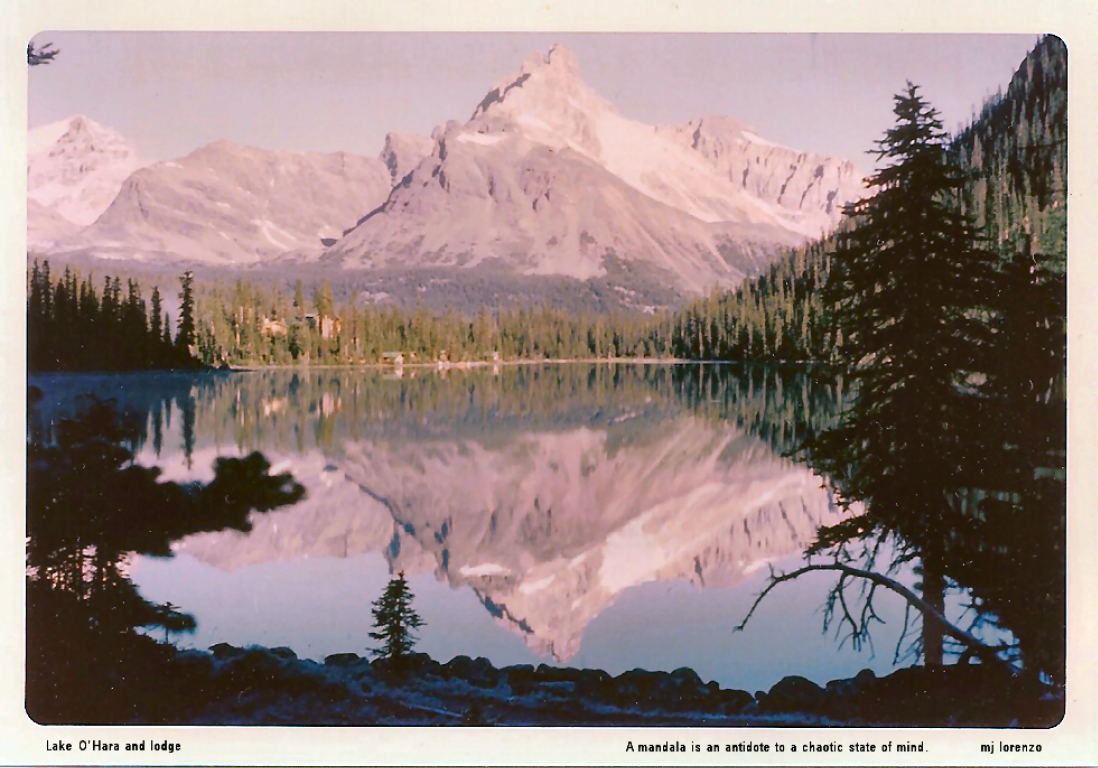

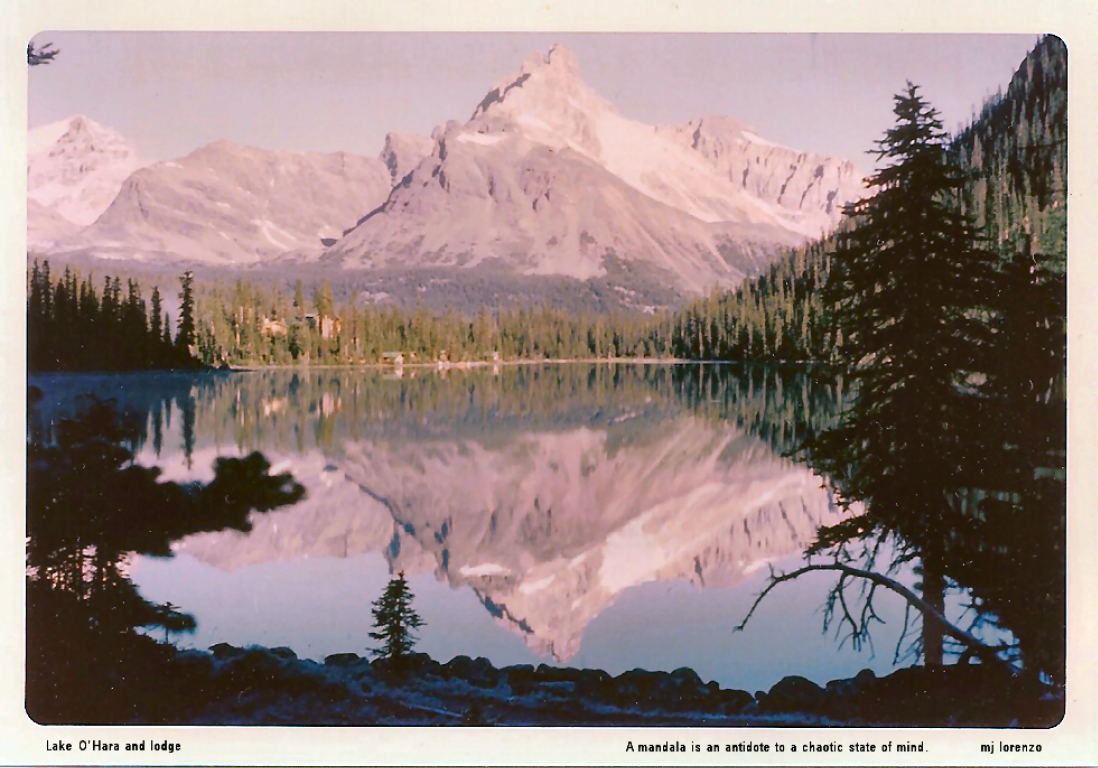

At the emerald

lake she bypasses

Precious time is

passing. The sky is bright blue already. It is cloudless;

crystal-sharp; pure.

She boards the

lake on its right side then cuts away into the evergreen

forest.

Two hours later

she emerges from trees onto the very high alpine plateau

called Opabin, looks back at the dazzling panorama for a few

seconds; the Yoho peaks in all directions; the green lake

still shaded way down and off to the right; the lodge and

tent in their green meadow far below at center; and

continues up the plateau along streams and around tiny

lakes, trampling with determination but not malice upon

Arnica, Labrador Tea, Valerian, Indian Paintbrush,

Cinguefoil, Dryas and Snow Lily, and brushing past

occasional feathery larch branches, oblivious to the

inviting perfume of evergreen or the lure of dewy grass.

She stops once to drink from a crystalline brook and

lets the water tug at her pony tail.

Her expression still is serious as she picks her way

cautiously over the ancient glacier at the head of the

valley, treading lightly around the crisply frozen edges of

deep, tummy-sinking blue crevasses, climbing constantly

higher toward the pass above, always planting her steps in

any boot-holes bearing mj’s distinctive tread.

Just before the pass Dlune glances left and straight

up at hulking Hungabee and flashes on her grandfather’s

face. She slips and crashes scraping bottom loudly on hard

ice, cries for a painful minute, then goes on.

At the top of

Up to her left is

She follows a stream

up to the foot of her ascent to

She sits down by the brook for a preparatory snack of

bread and cheese and water and lets the noon solstice sun

beat straight into her body through her skin, heating her up

until she has to rid herself of anything hot. She ties her

clothes to the top of the knapsack, throws the pack on her

back and sets out this time in nothing but heavy boots and

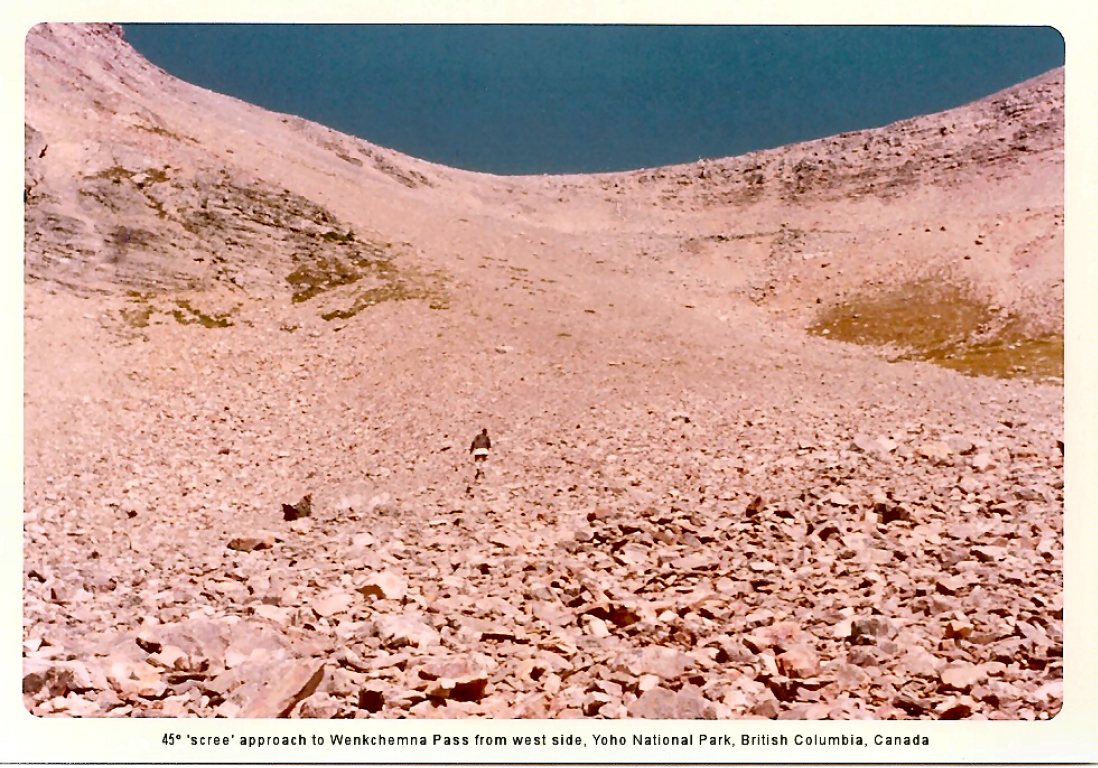

white hair-bow, to ascend a mile of ‘scree’ as steep as the

roof of her grandfather’s cabin.

During the first trying hour Dlune scales what looks

like half the distance. Her breasts bounce and droop

earthward each time a rock gives way beneath her and she

slides back. Several times she loses in thirty seconds of

slide all that she just gained from five minutes of delicate

climbing. Reddish scratches mark her legs and bottom

already. Open bleeding cuts ruin the knees. Indian blood is

left to dry on the rocks.

(Only: not quite as Indian as it might have been once back before white man ruined

it. Real squaw blood would have been pumping in a teepee back at camp.)

(No Indian brave ever required or

even allowed the

kind of hand-holding, double-checking and rescue-mission-ing

from a woman

that this white man had to have from Dlune. Not back when

there were real

Indian men anyway.)

During the second hour she covers what she thinks is

half the distance left and then finds a little rest on a

medium-sized boulder. She believes she can see the top of

the pass.

Toward the end of the third hour she thinks she is

almost there because the scree is thinning out, yet the

apparent distance to the ‘top’ has remained unchanged.

During the fourth hour she struggles less with rocks

by finding long stretches of lichen, loose dirt and solid

footing, but has to fight more wind. At the end of this hour

the angle of ascent lessens to 35° then 25° then

10°, until it levels out abruptly and drops again

rapidly eastward into ice-sculpted postcard-touted Moraine

Lake and the Valley of the Ten Peaks.

Dlune is unconcerned with beautiful vistas, however.

She is alone and miserable and wind is making her

perspiration evaporate too quickly.

Mj is nowhere in sight. She coughs twice and searches

for a remnant of him, convinced he must have descended the

other side. In the cold she replaces her clothes and cowers

from the wind, exposed unavoidably on Wenkchemna’s bare

shoulder, the base for climbing both peaks, Wenkchemna and

Hungabee

Both peaks are links in a long chain, two critical

vertebrae in a backbone called The Divide which stretches

north to south, pole to pole, splitting east from west.

Mj has told her that

‘Wenkchemna’ was probably Hungabee’s squaw, the tribal

chief’s wife: for the name has a ‘womanly sound’ to it.

And even a chief needs a woman

helping him at times, for all kinds of crazy things. A

chief more, in fact, according

to doctor mj. Because a chief, especially a medicine man

chief, needs crazier things, the very craziest things any woman might have to do for a man on the planet.

Because: she has to keep him from getting ‘infected by all

that craziness’ he has to deal with. She has to watch like

a hawk for any craziness getting too close to him.

But Dlune’s eyes

are too watery to see anything now.

Finally they dry

and she hawk-eyes one of mj’s notebooks, walks over, picks it

up and reads.